Connecting state and local government leaders

Cops are using secret cellphone trackers nationwide to collect cellphone data—especially in poor, black neighborhoods.

Louise Goldsberry, a Florida nurse, was washing dishes when she looked outside her window and saw a man pointing a gun at her face. Goldsberry screamed, dropped to the floor, and crawled to her bedroom to get her revolver. A standoff ensued with the gunman—who turned out to be an agent with the U.S. Marshals’ fugitive division.

Goldsberry, who had no connection to a suspect that police were looking for, eventually surrendered and was later released. Police claimed that they raided her apartment because they had a “tip” about the apartment complex. But, according to Slate, the reason the “tip” was so broad was because the police had obtained only the approximate location of the suspect’s phone—using a “Stingray” phone tracker, a little-understood surveillance device that has quietly spread from the world of national security into that of domestic law enforcement.

Goldsberry’s story illustrates a potential harm of Stingrays not often considered: increased police contact for people who get caught in the wide dragnets of these interceptions. To get a sense of the scope of this surveillance, CityLab mapped police data from three major cities across the U.S., and found that this burden is not shared equally.

How Does Stingray Surveillance Work?

Stingray phone trackers work by mimicking nearby cell towers and forcing phones to connect to them, extracting each phone’s location, number, and the phone numbers that outgoing calls and texts are being sent to within a certain radius. Stingrays can also capture the content of text messages and phone calls, though some police departments have claimed they are not using their devices to do so.

Civil-liberties advocates have criticized police for using Stingray phone trackers to seize location data from suspects’ phones, often without a warrant or even a disclosure that the device was used at all in later court proceedings.

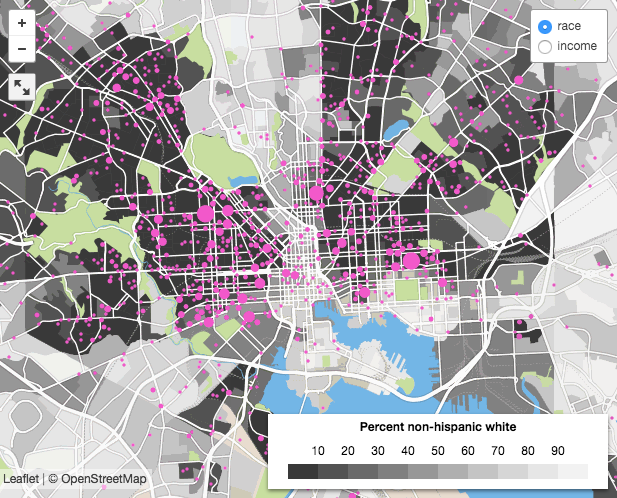

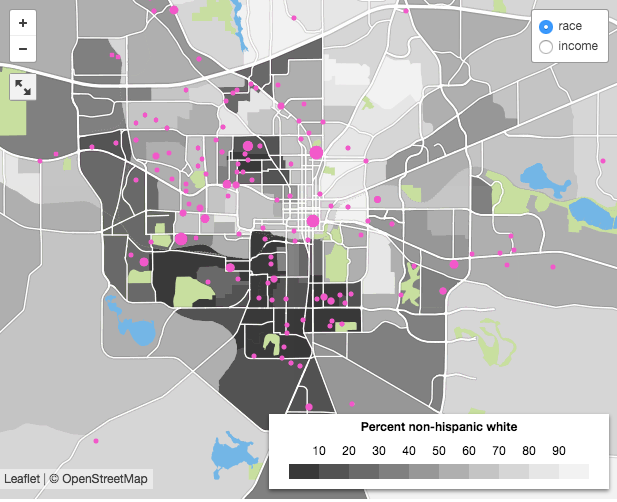

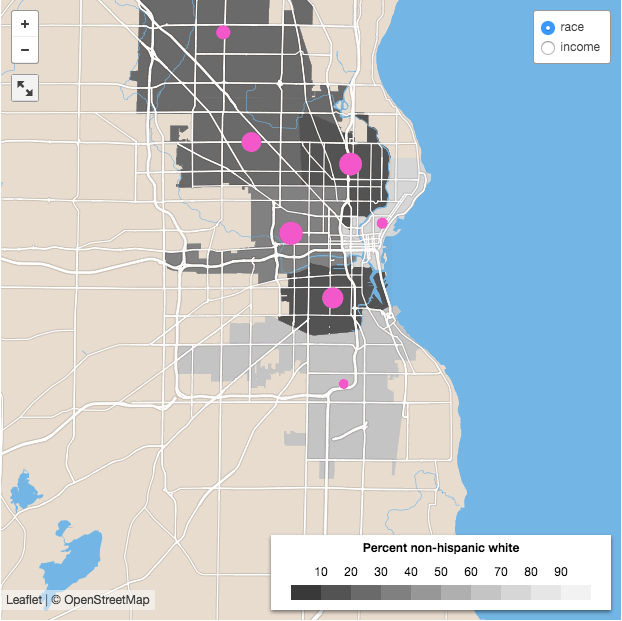

CityLab mapped police logs of Stingray operations in Baltimore, Milwaukee, and Tallahassee, using data obtained in separate inquiries conducted by USA TODAY, the Center for Human Rights and Privacy, and the ACLU. As shown in the maps below, police in these communities overwhelmingly use Stingrays in non-white and low-income communities. (These maps do not include all police Stingray interceptions in these cities, since some data on their use did not include geographic information. That data was not mapped.)

Mapping Stingray Use in Baltimore

In Baltimore, Maryland, 90 percent of Stingray incidents mapped occurred in majority non-white Census block groups, where residents are overwhelmingly African-American. Seventy percent occurred in Census block groups where the median annual income was less than the city's median annual income of $41,819, per 2014 Census data.

The purple dots on the map below represent the 1,740 individual uses of Stingrays by Baltimore police between 2007 and 2014 that resulted in the capture of a suspect and that could be geolocated. The dots that appear larger represent multiple Stingray uses, clustered at or near the same location.

Areas where Stingrays are deployed most are overwhelmingly in the city’s most intensely segregated non-white neighborhoods. (Seventy percent of Baltimore’s white population lives in majority-white block groups).

This marked racial disparity in surveillance becomes especially clear when looking at neighborhoods that are racially segregated, but that have roughly comparable incomes and crime levels. On the north-east side of Druid Hill Park, for example, are the historically white working-class neighborhoods of Hampden and Woodberry. On the south-east side of the park is Reservoir Hill, which, like the neighborhood directly to its west, Penn North, is mostly black.

Both Hampden-Woodberry and Reservoir Hill have significant numbers of lower-income residents, and unsurprisingly occasional robberies and assaultsoccur in each, yet police uses of Stingrays are far more concentrated in the mostly black Reservoir Hill.

Civil liberties groups recently filed a complaint to the FCC claiming that disparities like this suggest the Baltimore Police Department’s Stingray surveillance is racially biased. This charge comes on the heels of the Department of Justice’s recent finding that the BPD routinely engages in civil-rights violations.

Mapping Stingray Use in Tallahassee

In Tallahassee, Florida, Stingray surveillance also appears to hit low-income residents disproportionately, especially in the city’s non-white (mostly black) communities.

Of the 178 mappable Stingray uses carried out by local law enforcement in Tallahassee between 2007 and 2014, 53 percent occurred in majority non-white Census block groups, even though these block groups only accounted for 28 percent of the city’s total population. Moreover, 78 percent of these uses occurred within Census block groups whose median household income was less than Tallahassee’s median household income, which was $39,407 per 2014 Census data.

Mapping Stingray Use in Milwaukee

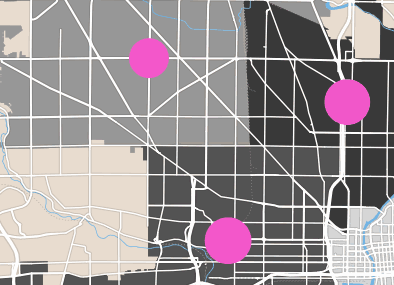

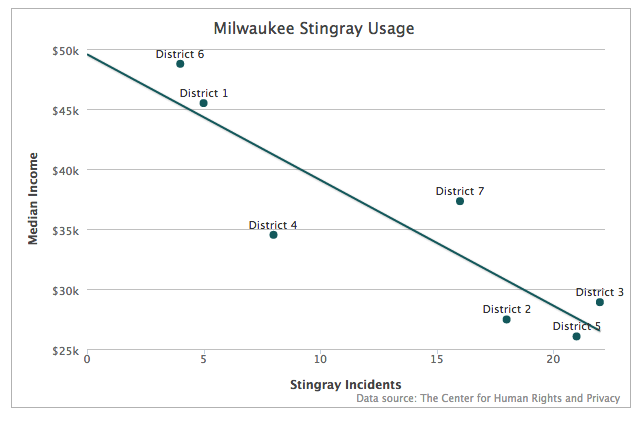

The numbers from Milwaukee also show apparent racial disparities in Stingray surveillance. This data—from 2010 to 2015—is mapped differently, however, because Stingray uses could only be geolocated by police district rather than by exact addresses; data points geolocated by outdated police-district boundaries were not mapped. Dots are sized according to the frequency of Stingray use per district.

Toggling between the race and income filters on the Milwaukee map, it is clear that though median incomes vary significantly in the city’s majority-black north side, Stingray use is spread more or less evenly throughout these neighborhoods.

In contrast, the city’s wealthiest (and majority-white) population concentrations—in Police Districts One and Six—experienced only a handful of Stingray uses each.

Stingray Data Use and Civil Liberties Violations

In Baltimore, Tallahassee, and Milwaukee, this disproportionate Stingray surveillance means that tens of thousands of people in low-income and majority-non-white neighborhoods are far more likely to have their locations and call data seized by police, even if they are not suspected of committing a crime. As GammaGroup, a Stingray manufacturer, explains in a brochure, “operating [a Stingray] within busy or crowded areas will result in many thousands of identities being acquired, most of whom will not be of interest or unwanted collateral.”

Law enforcement agencies, however, have frequently failed to disclose how information on “unwanted collateral” is being stored and potentially queried, as past court opinions have shown. And critics worry that this information will be stored and organized to create lists of “pre-suspects” when crimes occur in areas where Stingrays have already been used and pulled data.

“If you are in a certain neighborhood, you are going to encounter law enforcement a lot,” says Matt Mitchell, a security researcher with the racial justice organization CryptoHarlem. “So because of that, there are patterns that could be made between people and suspects who are not connected in any way. It’s making criminality viral.”

Tom Nolan, an associate professor of criminology at Merrimack College and a former Boston Police Department lieutenant, suggests that this “collateral” data poses serious civil liberties issues. ”Say I’m looking at a drug dealer on a corner, and we sweep up data on hundreds of people who happen to be in the vicinity. And then, at some later point, we realize there was some unrelated incident there, too… . Do I now have the right to access that data, even if we had no probable cause about any particular individuals?"

“We have to ask the question: ‘What are you doing with all that data?’,” says Malkia Cyril of the Center for Media Justice. “We don’t know—that’s part of the problem … . But given the fact that we already have racial disparities and parallel construction in police Stingray cases, we have to assume this data could be mobilized to put people under suspicion and in real danger.”

Nolan also points out that police could be using Stingray cases as an excuse to go on fishing expeditions for people’s data in hyper-policed areas. ”Who’s to say police aren’t running Stingrays constantly in ‘hot spot’ areas? ... Translation: communities of color,” says Nolan. ”The law-enforcement mentality is to get all the data and as much information as possible—Constitution be damned.”

Political Mobilization Against Stingray Secrecy

Given the secrecy with which police departments have used this technology, it is hard to know whether they are doing anything to address these concerns.

The Baltimore Police Department and the Tallahassee Police Department declined to comment for this story, and the Milwaukee Police Department did not respond to CityLab’s requests for interviews. All three departments have also signed non-disclosure agreements, required by the FBI, to keep their use of Stingrays secret.

Generally, law-enforcement leaders justify Stingray surveillance by claiming they use them to “find bad guys,” as FBI director James Comey argued at a media appearance last year. The data, however, suggest that Stingrays are often used to track low-level criminals rather than the terrorists and kidnapperspolice sometimes point to in justifying the procurement of the devices.

Between 2007 and 2014, of all Stingray uses by the Baltimore Police Department and the Tallahassee Police Department, 49.8 percent and 26.3 percent, respectively, related to cases of theft. Likewise, in Milwaukee between 2010 and 2015, 27.5 percent of Stingray uses by local law enforcement concerned theft cases. Homicide or murder cases (attempted or otherwise) during these same time periods made up just 13.9 percent of Tallahassee Police cases, 8.9 percent of Milwaukee-area law enforcement cases, and 12 percent of Baltimore Police cases where Stingrays led to the capture of a suspect.

Despite the increasing use of this technology for day-to-day crimes, police departments in all three of these cities have sought to hide their Stingray tracking. In March, a Maryland appeals court rebuked the Baltimore Police Department for failing to disclose that it used Stingrays to track down a suspect, and required that the department obtain a probable cause warrant to track cellphones going forward. Milwaukee and Tallahassee police have also been criticized in recent years for using Stingrays without warrants, and forfailing to disclose their methods of intelligence-gathering in court.

Public defenders and activists today are demanding that police be more transparent about this surveillance, and that they allow the public to decide how these tools should be used.

John Sawicki, a lawyer and forensics expert who has assisted public defenders in Tallahassee with several Stingray cases, shares the same concerns. “I’m not aware of any circumstance in Tallahassee where the police have come forward and said, ‘Hey, we used a Stingray.’ So how do you challenge a search that you never learned occurred?” says Sawicki. “Low-income areas aren’t any less entitled to good police work than anybody else.”

In September, a coalition including the ACLU, the NAACP, the Council of American-Islamic Relations, and the Million Hoodies Movement for Justiceannounced a plan to launch a legislative push in 11 major U.S. cities to promote greater transparency and community control over police surveillance tools, including Stingrays.

Maurice Mitchell, an organizer with the Movement for Black Lives, argues that the general public must do more to scrutinize Stingray surveillance, even if it is mostly confined to poor communities of color at the moment.

“Because the [surveilled] population is so marginal—young black people allegedly involved in criminal activity—people just don’t value the basic humanity of these folks enough to raise questions about their civil liberties,” says Mitchell. “But this is how police are able to bring this technology in. First into the black community—and then everywhere else.”

George Joseph is an Editorial Fellow at CityLab, where this article was originally published.

NEXT STORY: This Major Police Organization Just Formally Apologized for “Historical Mistreatment” of Minorities