Connecting state and local government leaders

Corporate goliaths are taking over the U.S. economy. Yet small breweries are thriving. Why?

The monopolies are coming. In almost every economic sector, including television, books, music, groceries, pharmacies, and advertising, a handful of companies control a prodigious share of the market.

The beer industry has been one of the worst offenders. The refreshing simplicity of Blue Moon, the vanilla smoothness of Boddingtons, the classic brightness of a Pilsner Urquell, and the bourbon-barrel stouts of Goose Island—all are owned by two companies: Anheuser-Busch InBev and MillerCoors. As recently as 2012, this duopoly controlled nearly 90 percent of beer production.

This sort of industry consolidation troubles economists. Research has found that the existence of corporate behemoths stamps out innovation and hurts workers. Indeed, between 2002 and 2007, employment at breweries actually declined in the midst of an economic expansion.

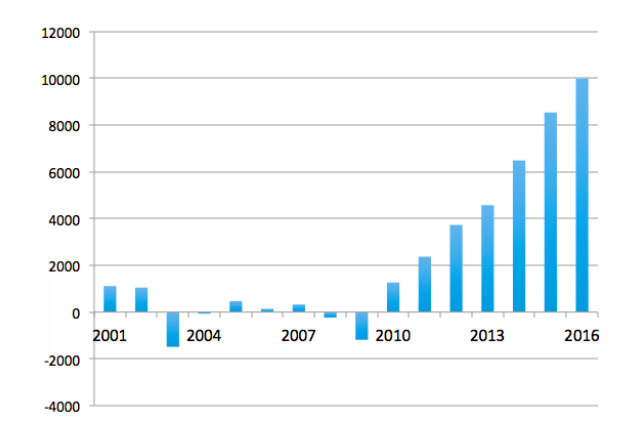

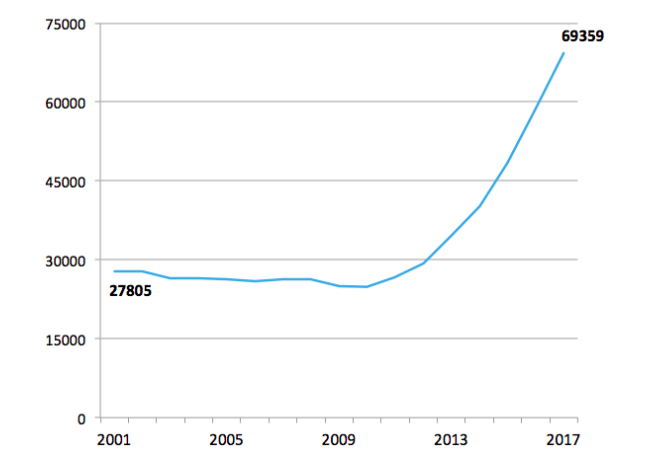

But in the last decade, something strange and extraordinary has happened. Between 2008 and 2016, the number of brewery establishments expanded by a factor of six, and the number of brewery workers grew by 120 percent. Yes, a 200-year-old industry has sextupled its establishments and more than doubled its workforce in less than a decade. Even more incredibly, this has happened during a time when U.S. beer consumption declined.

Net New Jobs at American Breweries, 2001-2016

Total Employment at U.S. Breweries, 2001-2017

Preliminary mid-2017 numbers from government data are even better. They count nearly 70,000 brewery employees, nearly three times the figure just 10 years ago. Average beer prices have grown nearly 50 percent. So while Americans are drinking less beer than they did in the 2000s (probably a good thing) they’re often paying more for a superior product (another good thing). Meanwhile, the best-selling beers in the country are all in steep decline, as are their producers. Between 2007 and 2016, shipments from five major brewers—Anheuser-Busch, MillerCoors, Heineken, Pabst, and Diageo, which owns Guinness—fell by 14 percent. Goliaths are tumbling, Davids are ascendant, and beer is one of the unambiguously happy stories in the U.S. economy. The same effect is happening at liquor distilleries and wineries. Employment within both groups grew by 70 percent between 2006 and 2016, thanks, in part, to the falling real costs of booze-producing equipment and the ease of advertising local businesses on social media.

When I first came across these statistics, I couldn’t quite believe them. Technology and globalization are supposed to make modern industries more efficient, but today’s breweries require more people to produce fewer barrels of beer. Moreover, consolidation is supposed to crush innovation and destroy entrepreneurs, but breweries are multiplying, even as sales shrink for each of thefour most popular beers: Bud Light, Coors Light, Miller Lite, and Budweiser.

The source of these new jobs and new establishments is no mystery to beer fans. It’s the craft-beer revolution, that Cambrian explosion of small-scale breweries that have sprouted across the country. The West is leading the way—cities with the most craft breweries include Portland, Denver, San Diego, Seattle, and Los Angeles—but the trend is nationwide. In Illinois and Idaho, brewing jobs grew by a factor of 10 between 2006 and 2016, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. According a BLS economist that I spoke with, 2016 was likely the best year for job creation at breweries in American history.

But what explains the nature of the craft-beer boom? From several interviews with economists and beer-industry experts, I’ve gathered that there appear to be two big reasons—a straightforward cause and a more complex and interesting history.

The first cause is something simple yet capricious—consumer tastes. “At the end of the day, the craft-beer movement was driven by consumer demand,” said Bart Watson, the chief economist at the Brewers Association, a trade group. “We’ve seen three main markers in the rise of craft beer—fuller flavor, greater variety, and more intense support for local businesses.” These factors are hardly unique to the beer industry. One could use the same descriptors to explain the concurrent rise of fast-casual restaurants, like Sweetgreen and Dig Inn, or the growth in expensive coffee from $5 lattes at Starbucks to a $55 cup of Esmerelda Geisha. There is, perhaps, a new trendiness to rare beer and expensive coffee that is luring new entrepreneurs into the space.

Craft breweries have focused on tastes that were underrepresented in the hyper-consolidated beer market. Large breweries ignored burgeoning niches, Watson said, particularly hoppy India Pale Ales, or IPAs, which constitute a large share of the craft-beer market. It’s also significant that the craft beer movement took off during the Great Recession, as joblessness created a generation of “necessity entrepreneurs” who, lacking formal offers, opened small-time breweries.

But the triumph of craft beer is not just about a preference for hops and sours. It’s also a story about America’s regulatory history, and how a certain combination of rules can make innovation bloom or wilt.

* * *

In the early 20th century, alcohol producers owned or subsidized many bars and saloons. These establishments were known as “tied houses,” since the bars were “tied” to the brewers and distillers. Tied houses were mortal enemies of the temperance movement. They were vertical monopolies that pushed down prices, got patrons drunk on cheap booze, and upsold them on gambling, prostitution, and other vices.

At the end of Prohibition, lawmakers felt that smashing these vertical monopolies was critical to promoting safe drinking. After the passage of the 21st Amendment, citizens in all states voted to abolish tied houses by separating the producers, like brewers, from the retailers, like bars. This led to a “three-tier system” in which producers (tier one) sold to independent middlemen that were wholesalers or distributors (tier two), who then sold to retailers (tier three).

By dividing the liquor business into three distinct groups, these state-by-state rules made the alcohol industry deliberately inefficient and hard to monopolize. “The great effervescence in America’s beer industry is largely the product of a market structure designed to ensure moral balances, one that relies on independent middlemen to limit the reach and power of the giants,” wrote Barry Lynn, the executive director at the Open Markets Institute, a nonprofit that researches antitrust issues.

The modern alcohol sector is specially designed to promote variety, in other ways. So-called “thing of value” laws make it illegal for beer producers to offer gifts to retailers in an attempt to purchase favorable shelf space. Other rules make it illegal for producers to buy shelf space, which saves room for smaller brewers to thrive at supermarkets and liquor stores. Altogether, these rules are designed to check the political and economic power of the largest alcohol companies while creating ample space for upstarts.

If the U.S. had long ago allowed a couple of corporations to take over both the distribution and retailing of wine before the Napa Valley renaissance, Lynn told The Atlantic in an interview, Americans would be exclusively sipping three varieties of Gallo table wine. “The reason that didn't happen 50 years ago is because you had this system that was designed to promote deconcentration, to incentivize [retailers] to go out and find the new, the different, the alternatives,” he said. “It was effective in achieving that aim.”

It was effective. Until it wasn’t. After Ronald Reagan’s election, the Justice Department relaxed its enforcement of antitrust laws. This kicked off a period of consolidation in various sectors across the economy, including the beer industry. Through a cavalcade of mergers in the last 30 years, 48 major brewers joined to form two super-brewer behemoths—Anheuser-Busch InBev and MillerCoors. Thus, an old system set up to avoid concentration became characterized by extreme consolidation.

But even as federal antitrust enforcement in the last 30 years has shifted to favor conglomerates, a groundswell has created the perfect conditions for the craft-beer revolution—or, more accurately, several distinct craft-beer revolutions. In the early 1980s, a smaller beer boomlet, featuring then-new breweries like Sierra Nevada and Samuel Adams, foreshadowed today’s larger craft craze. The timing was no coincidence. In 1978, Congress approved a resolution that legalized home-brewing, unleashing a generation of beer makers who experimented with flavors far more complex than the simplicity of Schlitz, Budweiser, and other basic brews that reigned for decades.

More recently, many states have made exceptions for small craft breweries to sell beer directly to consumers in taprooms. These self-distribution laws are controversial. Technically, they create an exception to the cherished three-tier system in a way that advantages smaller breweries. But economists and beer fans alike often defend these rules, since they can help small firms establish a fanbase and then phase out when a brewer makes it big.

* * *

So, what are the lessons of craft beer’s triumph for the rest of the economy? First, just as research shows that gargantuan companies are bad for innovation and job creation, the craft-beer boom shows that the burgeoning of small firms stimulates both product variety and employment. Second, sometimes consumers have their own reasons to turn against monopolies—particularly in taste-driven industries—just as they are moving away from Budweiser and popular light beers toward more flavorful IPAs and stouts produced by smaller breweries.

Third, even in an economy obsessed with efficiency, sometimes it is just as wise to design for inefficiency. Alcohol regulations have long discouraged vertical consolidation, encouraged retailers to leave room for new brands, and more recently made it easier for individuals to introduce their own batch of beer to the market. Those are the aims the country should adopt at the national level, both to make it easier for small firms to grow and to make it harder for large firms to relax.

A phalanx of small businesses doesn’t automatically constitute a perfect economy. There are benefits to size. Larger companies can support greater production, and as a result they often pay the highest wages and attract the best talent. But what the U.S. economy seems to suffer from now isn't a fetish for smallness, but a complacency with enormity. The craft-beer movement is an exception to that rule. It ought to be a model for the country.

Derek Thompson is a senior editor at The Atlantic, where this article was originally published. Joe Pinsker contributed reporting to this article.

NEXT STORY: State and Local Jurisdictions Step Up to Fill Federal Void During Shutdown