Connecting state and local government leaders

Supermajority tax measures have been pushed since the 1990s by deep-pocketed lobbying groups.

In Oklahoma, schoolchildren use tattered history books that say George W. Bush is still president, and a third-grade teacher is pan-handling to pay for class supplies. Some Colorado school districts can only afford to hold classes four days a week. One Arizona teacher is paid so little that she works three other part-time jobs to make ends meet.

America may be one of the world’s richest countries, but you wouldn’t know it to look at its public education system: U.S. public school teachers are among the worst-paid in the developed world. And many of the U.S.’s nearly 100,000 public schools have been crippled in recent years by tax cuts that slashed school budgets, cut salaries, and threaten teacher pensions.

Tens of thousands of teachers in Kentucky, Oklahoma, West Virginia, Arizona, and Colorado have staged walkouts and strikes in recent weeks. Louisiana and North Carolina teachers could be next. “We have a generation of students whose entire academic future has been thrown away for corporate tax cuts,” said Noah Karvelis, an Arizona music teacher and strike leader.

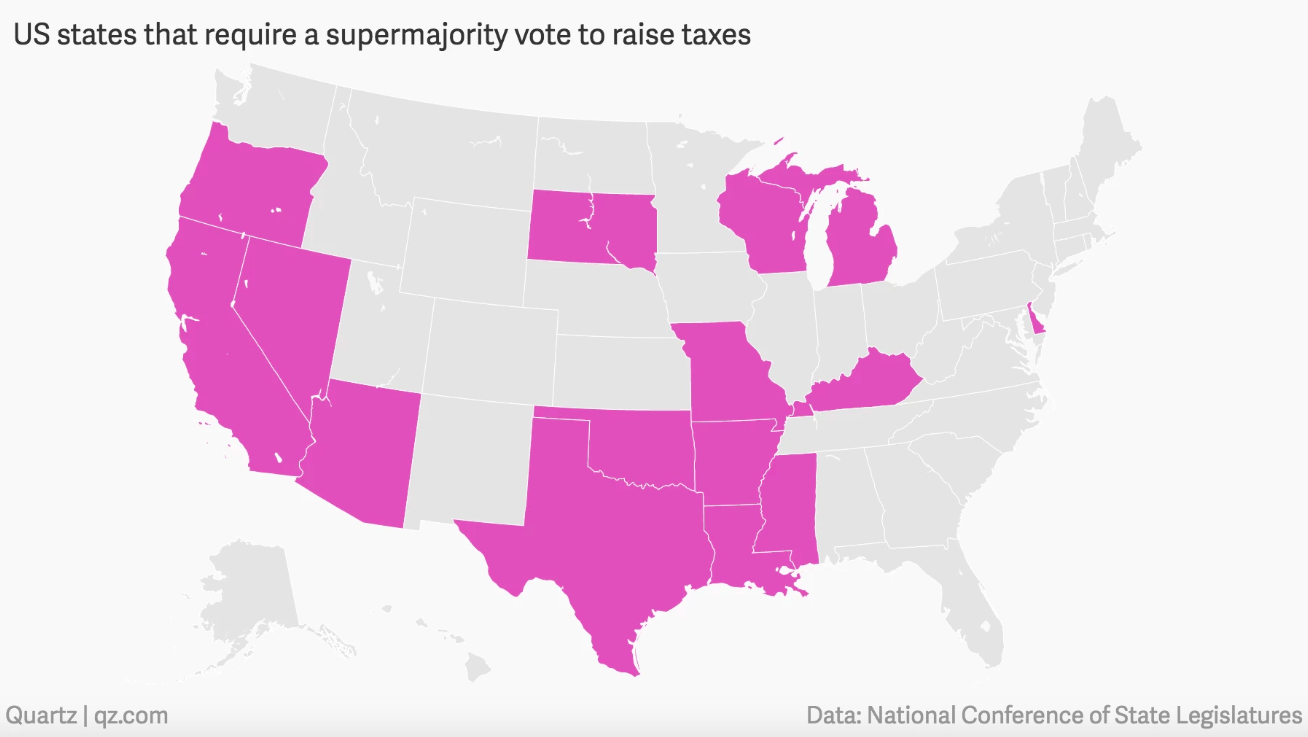

One way to invest more in books, schools and teachers would be to raise taxes. But most of the states with striking teachers face a special obstacle that makes that nearly impossible: “Supermajority” tax measures, which require a wider-than-normal margin of legislators to vote for tax increases. Cutting taxes in these states is easy, but reversing those cuts to fix problems like underfunded schools, is tough.

Supermajority laws are a “straightjacket for states,” depriving them of funding and flexibility, says Mary Bottari with the Center for Media and Democracy, a lobbying watchdog group.

These supermajority tax measures have been pushed since the 1990s by deep-pocketed lobbying groups, including Americans for Prosperity, and the conservative bill machine the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), both funded by Tea Party backers Charles and David Koch, wealthy donors, and some of the U.S.’s biggest companies.

Easy to Cut, Hard to Raise

To raise taxes in most U.S. states, lawmakers only need to get a simple majority of over 50 percent. To increase them in supermajority states, they need 60 percent or more of the local Senate and House.

That’s proven nearly impossible in mostly Republican states, where lawmakers have focused on tax cuts and small government for decades. It’s also tough in “purple” states, which have a mixed Democratic and Republican population.

“Our legislature has cut taxes every year since 1990,” said David Lujan, the director of the Arizona Center for Economic Progress and a former state lawmaker. The super-majority law has “definitely tied the hands of legislators,” making it “much more difficult to raise revenues,” he says. Arizona stripped $1.8 billion from public education between 2008 and 2014 alone, he notes.

Education funding is a major part of states’ expenditures, and teachers’ salaries make up a big part of that expense. Unlike the U.S. federal government, states can’t carry deficits from year-to-year, so they need to raise the money to pay their bills or cut expenses immediately.

A Growing Phenomenon

Over a dozen U.S. states can’t raise taxes without getting a supermajority of three-fifths to three-quarters of lawmakers on board, including Arizona, Kentucky, and Colorado. Florida, which already requires a three-fifths majority to raise corporate income taxes, is considering adopting such a measure across the board, while Colorado requires a popular vote to raise taxes, which has backfired as lawmakers try to work around it.

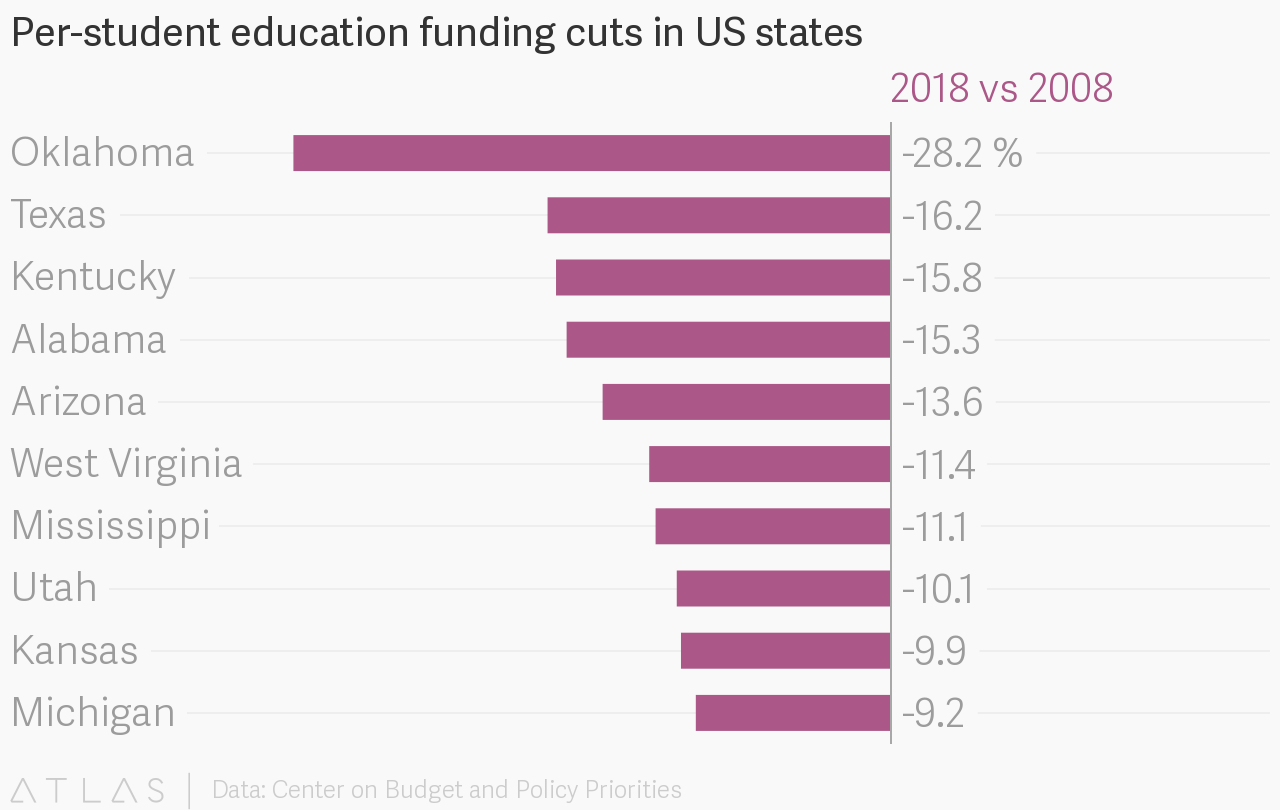

In Oklahoma, lawmakers cut the most per student from education budgets of any U.S. state in the past decade.

Oklahoma also has one of the most extreme supermajority laws in the country. There, 75 percent of lawmakers need to approve a tax increase, a threshold the 149-member legislature has been unable to meet since the law was passed in 1992—until late March this year, in a failed attempt to stave off April’s teachers strikes.

Oklahoma passed its supermajority law back in 1992, thanks to a consortium of businessmen led by the publisher of the Oklahoman newspaper. Arizona passed its law the same year, and since then has passed 38 different tax credits that strip an estimated $400 million a year from the state budget. Once passed, these credits are almost impossible to repeal due to supermajority requirements.

ALEC and Americans for Prosperity

ALEC lays out how the supermajority law works in a sample piece of legislation on its website that explains “the ability to raise taxes or enact new taxes should be made as politically difficult as possible, require broad consensus, and be held to a high standard of accountability.”

Section 1. Amend Article (number) of the Constitution of the state by adding a new Section thereto as follows:

(A) Imposition or levy of new taxes or license fee.

(1) No tax or license fee may be imposed or levied except pursuant to an act of the legislature adopted with the concurrence of two-thirds of all members of each House.

(2) This amendment shall not apply to any tax or license fee authorized by an act of the legislature which has not taken full effect upon the effective date of this bill.

(B) Limitation on increase of rate of taxes and license fees.

(1) The effective rate of any tax levied or license fee imposed may not be increased except pursuant to an act of the legislature adopted with the concurrence of two-thirds of all members of each House.

Supermajority bills have been “one of the holy grails” for ALEC and the Americans for Prosperity, said Nick Johnson, the senior vice president for state fiscal policy at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. “It has become almost a fundamental plank on the state level of the conservative hard right platform,” he said.

ALEC is hardly a household name, but it has a decades-long history of pushing hundreds of state laws to further a conservative agenda, from “Stand Your Ground” bills to laws against greenhouse gas limits. It brings companies and legislators together to write bills, and in 2015 counted one in four US lawmakers as members.

Run by a board of former and current Congress members and advised by private business people, some tied to Koch Industries, it has been receiving donations from the Koch brothers for years. “Like ideological venture capitalists, the Kochs have used ALEC as a way to invest in radical ideas and fertilize them with tons of cash,” wrote Lisa Graves, a former Department of Justice deputy assistant attorney general and head of the Center for Media and Democracy, in a 2011 investigation into the group. ALEC didn’t respond to several requests for comment.

Americans for Prosperity calls itself the “grass-roots” activism group that advocates for Koch brothers-backed ideas, but ALEC makes them law. ALEC’s bills are often introduced word-for-word in state legislatures, and are more likely to pass than other legislation, a 2013 Brookings Institution study found.

The Rationale Behind Super-Majority Laws

Supermajority bills were heralded as ways to ultimately improve economic growth, and force lawmakers to spend money more wisely. The idea is often buttressed by some variation of the “trickle down” theory of economics—cutting taxes encourages businesses to invest and hire more, and people with disposable income to spend more.

California’s “Stop Hidden Taxes” initiative of 2010, for example, was championed by the state Chamber of Commerce as a way to keep business in the state and “employ Californians, create jobs and generate revenue.” It strengthens a state supermajority tax bill, requiring a two-thirds majority to pass new fees for things like breaking environmental laws—and had the backing of everyone from Chevron to the local Wine Institute.

States enacted supermajority rules because voters are tired of elected officials “increasing the tax burden without first asking hard questions to better align taxpayers’ dollars with their priorities, such as treating teachers fairly,” Americans for Prosperity spokesman Bill Riggs told Quartz in an email.

“Teachers should be rewarded for the value they bring to children’s lives,” he said, but before rushing to raise taxes to do so, states should examine why education tax dollars don’t always go to teachers, he said, pointing to a study that found a seven-fold increase in administrative positions since 1950.

Lawmakers should be “examining that disconnect,” when they consider how teachers are paid, he said. “Without common-sense measures like supermajority protections, too many politicians will take the easy way out without addressing systemic problems.”

The Economic Reality

Making it harder to raise taxes hasn’t necessarily resulted in the economic growth or wiser spending that it was supposed to, however. While states that passed supermajority tax laws spent about 2 percent less on general state funding, that was offset by local spending (ie. from villages, cities, and counties), an Urban Institute report found (pdf, pg. 64).

There’s a broader lesson about “trickle down” economics that the U.S. seems to be learning again and again, since the phrase was first coined to mock president Herbert Hoover’s depression-era tax plan. “We’ve got a good base of evidence from tax cutting in the states that shows tax cuts are not a recipe for economic growth,” said Johnson. “They just lead to reductions in services that people need.”

States with supermajority tax rules that are desperate for cash instead push up other fees like increasing state college tuition and add court access fees like charging for public defenders.

On May 3, teachers in Arizona ended a six-day walkout after the state government agreed to a 20 percent salary raise over the next three years. While it sounds like a lot, it’s much less than what teachers were originally asking: Overall, Arizona’s school funding is still below the levels of the 2008 recession, later raises are not guaranteed, and and they’re being financed by cash set aside to clean up pollution.

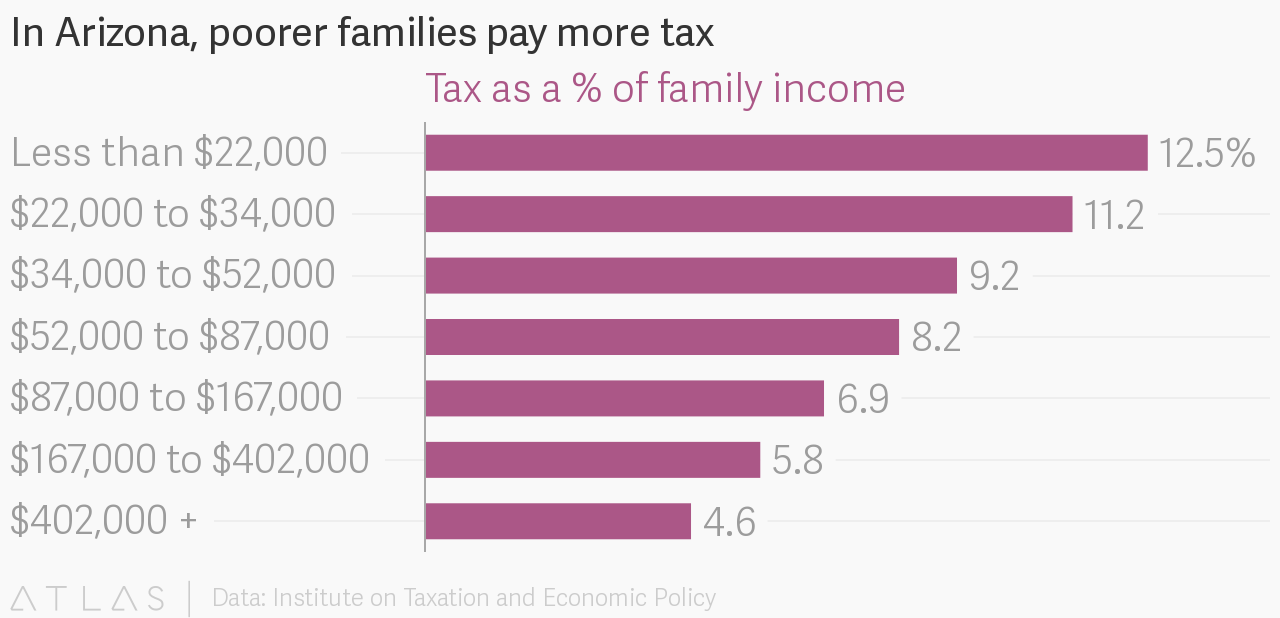

When lawmakers do gather enough votes to raise tax revenues, it is usually for “low hanging fruit” like cigarette taxes or a sales tax, said Meg Wielhe, the deputy director for the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, a tax research group. These increases “definitely fall more heavily on low-income families,” she said, which can means they pay a greater percentage of their income in tax overall.

A Building Backlash

Striking teachers believe they may be the forefront of a new grassroots movement in the U.S., one that makes voters reconsider taxing companies and the wealthy, and subsequently invest in communities again.

Coalitions are emerging to push back against these supermajority laws, made up of everyone from human service organizations to school boards to highway contractors and environmentalists, said Johnson from CBPP. Meanwhile, dozens of companies have cut ties with ALEC in recent years, under pressure from watchdog groups and news reports.

Some teachers who were on strike have adopted a new chant as they come off: “Vote them out.” They intend to go to the polls in huge numbers in the mid-term election, and vote against candidate running on platforms of tax cuts and caps.

More than 30 of members of the Oklahoma Education Association, which is made up of teachers and other school employees, are running for office in the November midterms, according to spokesman Doug Folks. People in Oklahoma are starting to realize “you can be a conservative,” Folks said, “and you can have some common sense about voting in some revenue funding.”

Healther Timmons writes for Quartz, where this article was originally published.

NEXT STORY: Decade After Recession Began, Tax Revenue Higher in 34 States