Connecting state and local government leaders

New Jersey is one of at least 25 states considering aid-in-dying bills this year.

This article was originally published by Stateline, an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts an was written by Michael Ollove

Susan Boyce, married and the mother of four, doesn’t know when she will die, but she knows how. One day, her diseased-decimated lungs will no longer be able to pump oxygen through her bloodstream.

“What happens with us is that we can’t get enough oxygen,” said Boyce, 54, of Rumson, New Jersey, who must take oxygen through a machine most of the day in order to breathe. “We die by suffocation. I don’t want to die by suffocation. It’s a slow, awful death.”

Which is why Boyce, whose condition causes her immune system to destroy healthy lung tissue, wants New Jersey to join the handful of states that allow physicians to prescribe lethal medications to dying patients.

New Jersey is one of at least 25 states considering aid-in-dying bills this year according to the Denver-based advocacy group Compassion and Choices, and advocates think momentum is on their side.

Support for aid-in-dying is increasing—a recent Gallup poll found two-thirds in favor, up from half four years earlier. Major medical groups have dropped or softened their opposition. And increasing life spans, while generally a positive development, mean that more Americans are watching their parents die drawn-out, agonizing deaths.

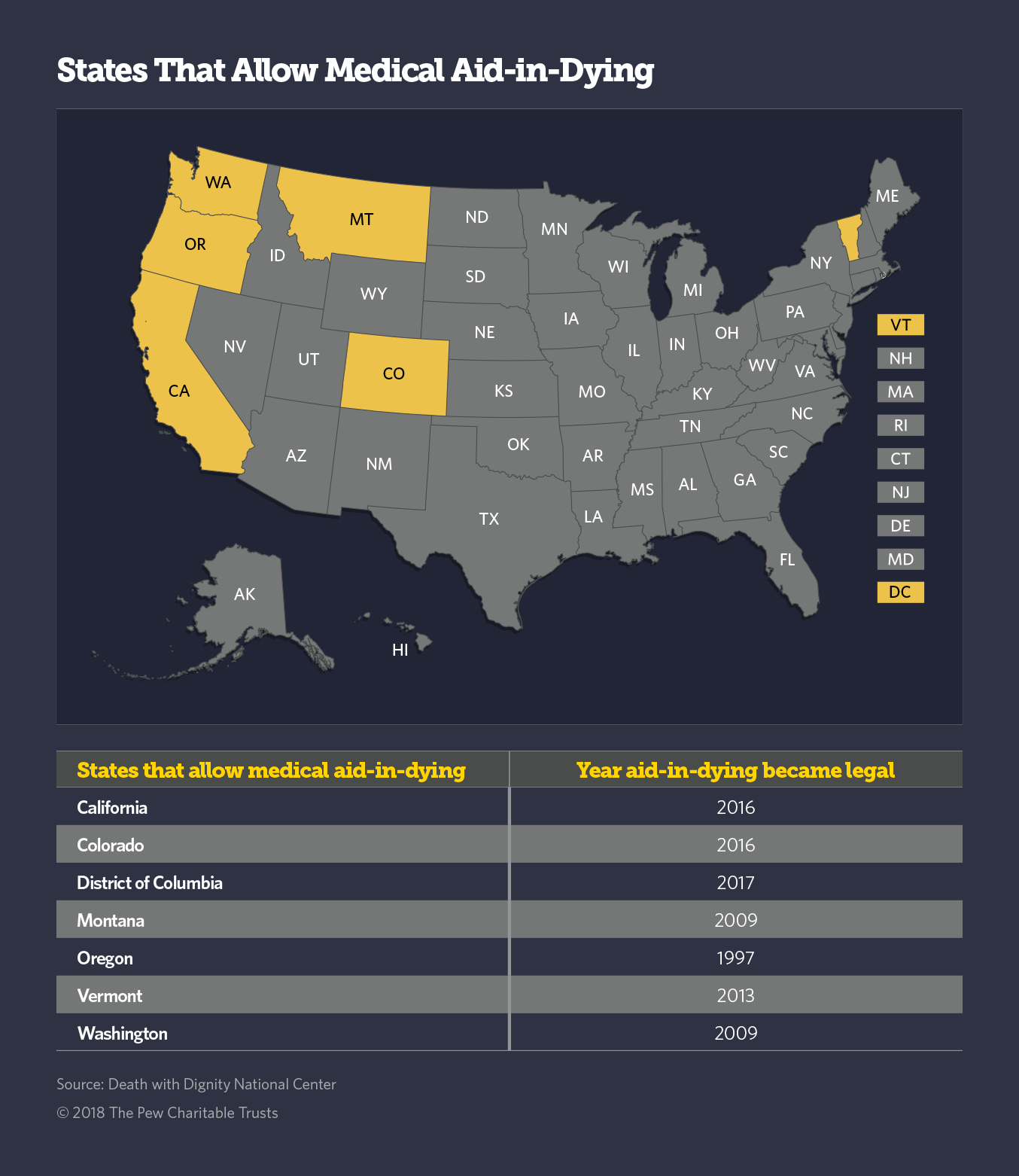

Oregon voters legalized aid-in-dying—sometimes referred to as “death-with-dignity” or “assisted suicide” — by approving a ballot measure in 1994 (a court injunction delayed implementation until 1997). Washington state voters followed suit in 2008 (it took effect in 2009), and a court ruling made it legal in Montana in 2009. Since 2013, Colorado, California, Vermont and the District of Columbia have legalized it, either through ballot initiative or legislation.

Advocates are particularly optimistic about a breakthrough in Hawaii where just this week the House sent an aid-in-dying bill to the state Senate on a 39-12 vote. They also expect success in New Jersey and perhaps in New York and Massachusetts as well, thanks to recent changes in the composition of the legislatures and, in the case of New Jersey, the governor’s office.

David Grube, an Oregon doctor in palliative care, which works to ease both physical and psychological pain of seriously ill or injured patients, once opposed aid-in-dying. But he said that as more states have legalized aid-in-dying and no evidence has emerged that patients are being pressured into the process, more people are becoming comfortable with the idea.

“It’s like same-sex marriage,” said Grube, who is the medical director of Compassion and Choices. “Forty or 50 years ago, I didn’t even know what a homosexual was. Now I see people in loving relationships, and that’s great.”

Even some critics of aid-in-dying acknowledge the momentum.

“Many of my colleagues have softened,” said Ira Byock, a Torrance, California, palliative care doctor who is chief medical officer for the Institute for Human Caring. The institute provides medical, spiritual and emotional support to seriously ill patients and their families as part of the Providence St. Joseph Health system.

Medical Groups Differ

Advocates point to several encouraging developments. The powerful American Medical Association remains firmly against aid-in-dying. “Physician-assisted suicide is fundamentally incompatible with the physician’s role as healer, would be difficult or impossible to control, and would pose serious societal risks,” the group says. Yet, 10 of its state chapters have dropped their opposition. For example, the Massachusetts Medical Society in December changed its position from opposed to neutral.

At the end of 2016, an online survey of 7,500 physicians from 27 specialties by Medscape, a news site on medicine, found that 57 percent were in favor of aid-in-dying.

Officially, organizations such as the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization maintain their opposition to aid-in-dying measures. But many individual practitioners have become more comfortable with the idea.

Many supporters credit as a turning point the extensive media coverage of the 2014 death of 29-year-old Brittany Maynard, who had an aggressive form of brain cancer and who promoted aid-in-dying before taking lethal medications prescribed by her doctor in Oregon.

“I really did believe that good palliative care could address the needs of people who were dying,” said Ann Jackson, the CEO of the Oregon Hospice Association from 1988 to 2008. But Jackson came to change her mind.

“The main thing I’ve learned is that that is not true,” said Jackson, who now consults on end-of-life issues. “We may be able to address pain and symptoms, but we cannot address the futility some people feel at the end of life, the suffering they feel over their loss of autonomy. Hospice care cannot allow people to control their lives if they are going to deny them the right to die at a time of their own choosing.”

The Catholic Church remains firmly opposed to aid-in-dying, as do many organizations that represent people with disabilities.

“Mistakes by health care professionals, widespread misinformation, coercion and abuse limit the opportunity for people with disabilities to make informed and independent decisions,” the American Association of People with Disabilities says in its statement about aid-in-dying.

“The legalization of assisted suicide devalues the lives of people with disabilities,” the group says. It argues that some of the disabled could be coerced into agreeing to assisted suicide.

Even if there is institutional opposition, polling in 2014 by the public opinion company Purple Strategies has indicated majority support for aid-in-dying among Catholics and people with disabilities in Massachusetts and New Jersey.

One study of physician-assisted dying in Oregon and the Netherlands found no evidence that the practice was used more frequently on people with disabilities or those in other “vulnerable” groups, such as the poor and racial and ethnic minorities.

Oregon the Model

Nearly 18 percent of Americans live in places where aid-in-dying is legal. (Washington, D.C.’s law is in jeopardy. The U.S. House Appropriations Committee last summer passed an amendment from Republican Rep. Andy Harris of Maryland that would nullify the D.C. law. If the House incorporates the amendment in its 2018 federal spending bill, it would doom the D.C. law.)

Most state measures are modeled on Oregon’s law, which outlines steps for patients who want assistance in death: The patient must be a state resident, at least 18, still able to communicate, and diagnosed with a terminal illness with a prognosis of six months or less.

Patients must make two separate oral and one written request to their physician. The prescribing physician and a consulting physician must confirm the diagnosis and prognosis and determine whether the patient is capable of making a decision and isn’t impaired by a mental disorder. And the prescribing physician must inform the patient of feasible alternatives to medical aid-in-dying, including hospice care and pain control.

Oregon closely tracks how the law is used. Since the law’s enactment, 1,967 people received legal prescriptions under the law, and 1,275 ingested the medication. Oregon data shows the median age for people who took this option in 2017 was 74.

Byock said he believes doctors who provide aid-in-dying are violating the most sacred stricture in medicine. He also believes that in most cases, it is possible to provide pain relief to dying patients, and that the real problem is that quality palliative care is not universally available or embraced by the medical profession. He believes training in palliative care should be mandatory at medical schools.

Byock also points out that the biggest concern of Oregon patients who used the law was not escape from pain, but their decreasing ability to enjoy their lives, loss of autonomy and loss of dignity, according to an Oregon report on its use. “Plenty of other people face those same conditions,” said Byock, including those with severe arthritis, depression or failing eyesight. “Once we go down this road, it’s a slippery slope.”

In Oregon, however, it was not because they couldn’t get end-of-life services that patients turned to aid-in-dying. About 90 percent were enrolled in hospice at the time of death, according to the most recent state data, published last month.

Byock acknowledges palliative care can’t always take away pain. It didn’t for T.J. Baudanza Jr., a onetime marketing manager who in 2015 died of colon cancer at age 32 in New Seabury, Massachusetts. “T.J. died the way he feared he would,” said Amanda Baudanza, his widow, in an interview. “He suffered a prolonged, painful death because Massachusetts denied him the option of medical aid-in-dying.” He was in hospice in the last portion of his life.

T.J. had been a big supporter of an aid-in-dying referendum that narrowly missed passage in Massachusetts in 2012, not long after his diagnosis. Now Amanda is championing aid-in-dying in the state Legislature.

“I’m Catholic and so was T.J.,” Amanda said, “but he and I both believed that God wouldn’t want anyone to suffer needlessly.”

In New Jersey, Susan Boyce says her lungs are doing well enough that she believes her death is still off in the distance. She hopes to travel from her home in Rumson to Trenton to testify on behalf of the bill later this month.

Boyce doesn’t know if, when the time comes, she actually would take medicine that would end her life. But she knows one thing. “I want the option.”

NEXT STORY: The Mayor’s Life at SXSW