Connecting state and local government leaders

The ride-hailing giants confess that they are indeed increasing congestion in several U.S. cities. But private cars, the companies insist, are the real problem.

After the 2008 economic crash, Americans began driving less. But it didn’t last long: In every year since 2013, U.S. drivers have packed on more miles behind the wheel. This rise in vehicle-miles traveled (VMT, in wonk-speak) can be seen and felt in the nation’s metropolises. Congestion on major arteries like L.A.’s I-405 or San Francisco’s Geary Boulevard is getting worse; pedestrian death counts are reaching record heights; tailpipe emissions are growing thicker.

Also new since the Great Recession—Uber and Lyft. These ride-hailing services stormed into cities in the 2010s with a grand utopian promise: By tapping into America’s vast reservoir of idle vehicles, on-demand, app-based rides would reduce the need for personal car ownership and ultimately remove cars from the road.

But now, less than a decade into this experiment, the industry is ‘fessing up. Today the ride-hailing giants released a joint analysis showing that their vehicles are responsible for significant portions of VMT in six major urban centers. And though Uber and Lyft’s combined share is still vastly outstripped by personal vehicles, they are “likely contributing to an increase in congestion,” as Chris Pangilinan, Uber’s head of global policy for public transportation, wrote in a blog post accompanying the findings.

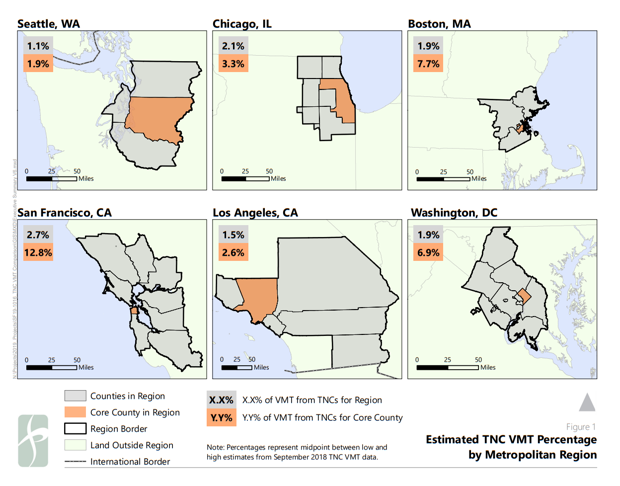

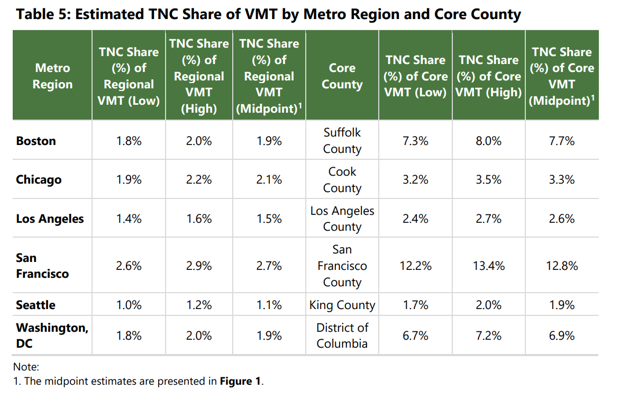

Led by the respected transportation consultancy Fehr & Peers, the analysis provides a high-level view of the combined mileage contributions from Uber and Lyft, as a share of overall VMT, over a recent month in the Boston, Chicago, L.A., San Francisco, Seattle, and Washington, D.C. areas. Results are shown at the level of the larger metropolitan landscape, which includes both the central city and its surrounding suburbs, as well as the level of the core county that contains the city’s most concentrated homes and jobs.

Notably absent here: New York City, the largest U.S. market for these “transportation network companies,” or TNCs. A Lyft representative said that this was partly because the city is a unique in terms of its extremely low rate of car ownership and expansive transit system. Previous research by the independent transportation consultant Bruce Schaller has shown that yellow cabs and TNCs together make up 50 percent or more of traffic in central Manhattan—findings that pushed New York City lawmakers earlier this year to approve congestion fees for drivers entering the downtown core.

The new findings show that Uber and Lyft account for just 1-3 percent of total VMT in the six larger metro regions. But they have a much heavier traffic impact in core urban areas, as the table below shows: In San Francisco County, Uber and Lyft make up as much as 13.4 percent of all vehicle-miles. In Boston, it’s 8 percent; in Washington, D.C., it’s 7.2 percent.

These numbers suggest that ride-hailing is hitting traffic harder in many cities than previously understood. For example, independent research by the San Francisco County Transportation Authority in 2017 showed that, as of fall 2016, TNCs generated about 6.5 percent of the county’s total VMT on weekdays, and 10 percent of weekends. And the agency found that the grown in ride-hailing was already a major contributor to noticeable slow-downs on San Francisco streets.

Now, the Fehr and Peers memo indicates that TNCs accounted for nearly twice the VMT in San Francisco than the SFCTA had estimated, said Gregory Erhardt, a professor of civil engineering at the University of Kentucky who has researched Uber and Lyft’s effects on public transit ridership. That means the services are likely delaying commuters more, too. “This difference may be due to the continued increase in TNC use over the intervening two years,” he said. “With nearly double the TNC VMT, we would expect the effect of TNCs on congestion to be much higher in 2018 than was estimated for 2016 conditions.”

Ride-hailing did not seem to have an equally large footprint in all cities. Uber and Lyft had lower shares of total VMT in L.A., Seattle, and Chicago.

The findings also answer a question that many transportation researchers have been keen to find out: How many TNC miles account for an actual passenger, versus an empty backseat? It might be even fewer than other researchers have guessed. On average, between the six cities, just 54 to 62 percent of the vehicle miles traveled by Lyfts and Ubers were with a rider in tow. A third of these miles involve drivers slogging around in between passengers (“deadheading,” in taxi-driver argot); 9 to 10 percent are drivers on their way to a pickup.

There are other big questions that go unaddressed here, such as the growth of Uber and Lyft traffic over time (other than the fact that they both started from zero, less than ten years ago), or their influence on riders shifting away from buses and trains. Erhardt would prefer to see the companies divulge more fine-grained information to allow for more independent review. And Schaller questioned the data itself, saying that he wouldn’t expect L.A. and Seattle to be such outliers.

Even so, these results represent a striking, if perhaps belated, confession from an industry that’s had a profound effect on urban life. As Uber and Lyft have grown from unicorn startups to publicly traded juggernauts with millions of daily riders, they have fought to keep their trip data out of the hands of regulators and researchers trying to measure the effects of ride-hailing on transportation networks. What numbers were available have painted an increasingly unflattering picture. Studies from U.C. Davis, the University of Kentucky, DePaul University, and independent researchers in Boston, San Francisco, and New York City have offered evidence that mobility apps contribute to VMT, congestion, and the decline of public transit ridership.

Meanwhile, it’s become harder for the companies to stand by their original traffic-taming claims. In 2018, Lyft collaborated with the Rocky Mountain Institute, a clean-energy think tank, to produce a study that concluded ride-hailing vehicles were “more efficient” than private cars in several cities. But after vociferous criticism, the claim that was later retracted. “We represented certain conclusions as definitive, when in fact they are not,” the Institute wrote. Now, Fehr and Peers write that their analysis should help both Uber and Lyft “form appropriate narratives for both internal and external communication.”

But, alongside their big mea culpa, Uber and Lyft are also pointing their fingers elsewhere, and justifiably so. The report calls out private vehicles as the true culprits in overall traffic congestion, accounting for 97 to 99 percent of total VMT in the analyzed regions. Indeed, across the U.S., 75 percent of Americans still drive alone to work.

As such, the ride-hailing companies are positioning their analysis as a way to promote congestion pricing, a policy where drivers pay fees to access high-volume city streets. Recently adopted in lower Manhattan, the model has been proven to reduce traffic in other parts of the world, and Uber and Lyft would love see more U.S. cities adopt it, since it could nudge riders to share trips. “We know other communities are beginning to study congestion pricing as a solution to traffic,” writes Anthony Foxx, the former U.S. Secretary of Transportation who is now Lyft’s Chief Policy Officer. “This has encouraged us to think more comprehensively about how to best implement congestion pricing.”

But for researchers who’ve spent years seeking the truth about ride-hailing, Uber and Lyft’s fresh numbers come as a valuable contribution. “It’s great to see them be upfront,” said Schaller. “I’m a scrounger for any information I can get my hands on. This is straight from the companies, and it’s very useful—it helps advance our understanding.”

Laura Bliss is CityLab’s west coast bureau chief.

NEXT STORY: Electric Scooters Good for the Planet? Only If They Replace Car Trips