Neighborhoods With More People of Color Pay Higher Energy Bills

The Wagner Public Housing complex in New York City. When the authors compared data from 4,000 subsidized housing and market-rate units throughout New York City, finding that the low-income units had “statistically significant” higher EUI levels. Wikimedia Commons

Connecting state and local government leaders

Not only are residents of minority neighborhoods paying more of their income for energy bills, but federal government housing policies are a huge part of the reason why.

It is well-established that the lower a family’s income, the more that family will pay for lighting and heating the house, running appliances, and keeping the wi-fi on. Such outcomes would suggest that this is a class problem or a function of rational markets. But according to a new study, all low-income households are not equally yoked: Residents of poorer, predominately white neighborhoods are less energy-cost burdened than people in predominately minority neighborhoods of similar economic status. Race matters.

Residents of minority neighborhoods who make less than 50 percent of area median income (AMI) are 27 percent more energy-cost burdened than residents from the same wage bracket who live in white neighborhoods. This is one of the findings from the study, “Energy Cost Burdens for Low-Income and Minority Households,” recently published in the Journal of the American Planning Association and conducted by New York University urban planning researchers Constantine E. Kontokosta and Bartosz Bonczak, and University of Pennsylvania urban planning professor Vincent J. Reina.

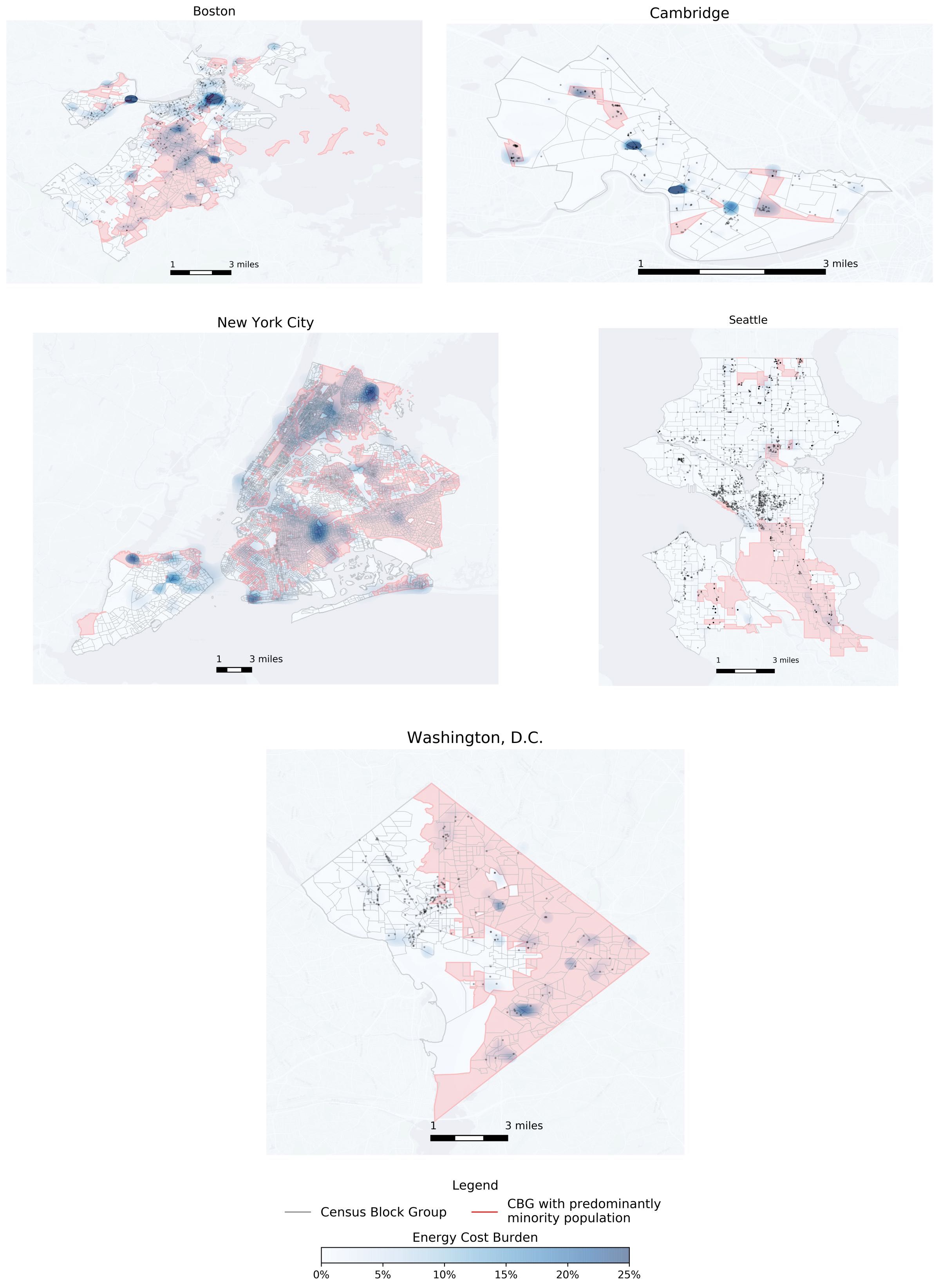

The research team analyzed energy consumption data from an estimated 13,000 apartment buildings across five cities—Boston, Cambridge, New York City, Seattle, and Washington, D.C.—taking advantage of energy disclosure ordinances in those cities, across census blocks and even at the individual building level.

At the census block level, they found energy cost burden disparities between white and minority neighborhoods not only for the lowest-income families, but also for households whose incomes fall within 51 to 80 percent of AMI and 81 to 120 percent of AMI. In these brackets, families in minority neighborhoods are more energy cost burdened by an average of 24 percent. In New York City and D.C., researchers found that residents of minority neighborhoods were more cost-burdened even at middle-class incomes, or 121-to-150 percent of AMI.

“Regardless of income, if that disparity exists, then if nothing else, it’s just a consistent statement of the fact that it’s race,” says Reina. “We care from an environmental perspective about all of our consumption levels, but from an energy justice perspective, we particularly care about the lowest-income households because those have the least agency in making decisions that can actually affect their consumption levels.”

The findings confirm other studies that energy burden inequities are driven in part by racial segregation, such as work from the Urban Energy Justice Lab, which drew similar conclusions when looking at Kansas City and Detroit. They also confirm studies, such as those done by the American Council for an Energy Efficiency Economy, that show that the poorest families are paying a larger share of their income than wealthy families: Reina’s research shows that lower-income households are spending between 10 and 20 percent of their wages on energy bills in these cities compared to wealthy families who pay on average between 1.5 and 3 percent of their income on energy.

The metric to understand here is energy use intensity, or EUI, which is the amount of energy a household uses per square foot. While white households consume more energy overall, black and Latino households have higher EUI, usually as a result of segregation where minority families dwell in neighborhoods with older housing stocks and smaller units.

Reina’s team found that households from both the lowest and highest income brackets had the highest EUIs in the cities they studied, but the reasons differed. For wealthier households, high EUI was a function of their own behavior—having more appliances and electronic devices with heavier usage of each, or even just leaving lights and the heat on because they can afford to. Energy efficiency programs and technology could bring down their EUI, but these households could also just modify their behavior or their consumption habits for reductions, as well.

On the other hand, poorer households could modify their habits all they want and would still have high EUI, because for these households, EUI is often a function of having larger families or more people living within a relatively small unit, like an apartment, with inefficient heating and lighting infrastructure. Although this demographic is often told to change their behavior, much about their EUI is out of their control. Reina’s study shows how using data from energy audits and energy disclosure laws can help city officials better craft energy efficiency policies that target the buildings and families who most need them.

Yet higher EUIs among lower-income households are also an outcome of how government regulates their living situations. It’s housing policies that are the problem, particularly when it comes to subsidized and public housing. The financing structures for government-subsidized affordable housing are set up so that they don’t incentivize the developers and owners of affordable housing to make energy efficiency investments, according to earlier research from Reina and the New York University Furman Center.

In a previous study, Reina and Kontokosta compared data from 4,000 subsidized housing and market-rate units throughout New York City, finding that the low-income units had “statistically significant” higher EUI levels than similar market-rate units. They compiled energy data from several kinds of subsidized housing: public, Section 8 or rental voucher, and low income housing tax credit (LIHTC) financed. Of the three, public housing, which is generally owned and operated by federal and local government housing authorities, had the highest EUI—15 percent higher than market-rate homes. Section 8 voucher housing’s EUI was 9 percent higher, and LIHTC-funded housing’s was 7.6 percent higher than market-rate units.

These results are not surprising given how the housing subsidy arrangements work. For public housing and Section 8, the federal government mostly funds the owners of the buildings—local housing authorities and landlords, respectively—through rent subsidies, which includes utility allowances to help cover electric bill costs. There is no real incentive for these building owners to invest in energy efficiency upgrades because the federal subsidies will at some point adjust to cover whatever increases occur in tenants’ electricity costs. Meanwhile, both are limited in how much they can increase rents: They can’t simply increase rent to cover whatever expenses come from installing new energy efficient equipment.

As for the tenants, when their electric bills go up, their rent goes down, so there’s little motivation there for them to conserve. Building owners could sub-meter their units, so that tenants had meter readings for their own unit and were responsible for paying for their own individual electricity use, as opposed to one meter covering the entire building. That way tenants would be motivated to conserve energy. But again, the federal subsidy project doesn’t give building owners a lot of reason to go that route. Reads the report:

HUD does not provide a benchmark for determining what a reasonable utility allowance is, and there is no feedback mechanism for what one's utility consumption “should” be. In aggregate, this utility allowance adjustment system shields households from the repercussions of overconsumption, and in doing so reduces their desire to reduce energy consumption or shop for a more efficient unit (if they could). The owner receives the same overall amount for rent plus utilities, regardless of the utility allowance amount, which also makes them indifferent about making energy efficient investments. Combined, these factors mean that in the Public Housing and Project- based Section 8 programs there is no pricing incentive for the landlord to increase the efficiency of the unit, or for tenants to reduce consumption levels.

This is why federal affordable laws should be changed to require subsidized housing to have sub-metering, a 2015 working paper from the NYU Furman Center argues: so that tenants are responsible for their own unit’s energy consumption. HUD could still provide utility allowances for tenants, but it would need to be right-sized to ensure that its covers the costs of the individual tenant, as opposed to the average energy costs of a whole building, as is currently practiced. The Furman Center also recommends that HUD do more to incentivize building owners to make energy efficiency investments in the properties.

Last week, New York U.S. Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Vermont U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders unveiled the “Green New Deal for Public Housing Act,” which would splurge on energy retrofits for mostly federal public housing developments, to the tune of $180 billion. The goal is to address the energy justice issue that Reina’s research identifies, while also making the greenhouse gas reductions needed in buildings to curb climate change.

Several other presidential candidates have released multi-billion dollar plans for affordable housing—including most recently, a bill from U.S. Representative Ilhan Omar to invest a $1 trillion in new top-grade public housing.

Many of these plans take into account that the poorest and non-white households are carrying the heaviest energy burdens. However, more cities and states need to adopt energy disclosure laws like the ones passed in Boston, Seattle, and New York City, so that housing authorities can better understand how energy is consumed at the building and housing unit level, and so those investments can be best allocated.

“We wanted to provide a more nuanced kind of estimate of energy cost burdens and to highlight the importance of disclosure data laws,” says Reina, “and how you can use that data to identify these phenomenon.”

Brentin Mock is a staff writer for CityLab.

NEXT STORY: The West’s Population Boom Leads to Development Backlash