Connecting state and local government leaders

Forward-thinking public officials and open government advocates are updating outmoded, inflexible digital platforms that host local and state legal codes.

As part of its regular social media routine, the District of Columbia Council’s official Twitter feed periodically links to obscure or odd provisions of the D.C. Code, like rules governing jostling rights: “Jostle away, but only if a breach of the peace may NOT be occasioned,” the Council’s Twitter feed informed its followers in June.

It may not seem like a big milestone, but the fact that D.C. Council staffers — or anyone for that matter — can simply link to a specific section of the D.C. Code is cause for celebration in digital circles.

Until relatively recently, permalinking, which has been a routine Internet function for years, had been out of reach for those working with the D.C. Code.

While information portals like Westlaw and LexisNexis — the latter of which hosts the District government’s law code — are paid to be repositories for local government information, their platforms routinely frustrate Web developers, public officials and open government advocates. In some cases, because of their contractual obligations, local governments are prohibited from releasing the raw data of their jurisdiction’s official law code, legislation and regulations, which can limit access to public information.

As a result, many state and local governments around the nation are stuck with outdated and inflexible digital platforms to host their official law codes.

“They were all probably really cool back in 1994, but then they stopped working on them,” said Waldo Jaquith, the director of the U.S. Open Data Institute and developer behind two Virginia-focused websites, Richmond Sunlight, which tracks bills and information related to the state’s General Assembly, and Virginia Decoded, which hosts an unofficial but highly functional version of Virginia’s code.

Virginia and the District of Columbia, working with open-data advocates, are two examples from among a handful of local jurisdictions around the country that have made efforts to unlock their official law codes. Those efforts have put the codes in more flexible and tech-friendly formats that are easier to search, link within and build upon for future uses.

The District is part of small coalition of proactive municipalities and open-government advocates around the nation that is seeking to make it easier for jurisdictions everywhere to host their official law codes, legislation and regulations on open-source technology. The group been hosting weekly conference calls to compare notes on their respective efforts, discuss common challenges and strategize about what comes next.

“We hope that this isn’t a flash in the pan and want something that’s sustainable over the long term,” said V. David Zvenyach, the D.C. Council’s general counsel. He has developed coding applications in his official position and on his own, and is a member of the open-data “free law” coalition, which also includes local government officials in Boston, Chicago, New York City and San Francisco. “We hope that other states and municipalities can benefit and contribute.”

D.C. and the CDs

D.C.’s experience unlocking its law code took a curious path. It started with a seemingly simple citizen’s request that ended up having a not-immediately accessible solution. But it came at an opportune moment, involved ancient CD-ROM technology and has even ended up serving as a technological base for one foreign government’s law code.

“There’s a zero percent chance that I’d be working on this right now if it hadn’t been for Tom MacWright,” Zvenyach told GovExec State & Local. “He changed my life.”

Back in August 2012, MacWright, an open-source mapping tools developer with Mapbox, was simply trying to find regulations governing the licensing process for D.C. restaurant valet stations. He had noticed one was impeding the flow of bicyclists in a bike lane he regularly used.

MacWright couldn’t link to the measure in Westlaw’s online portal, where the District’s official laws lived digitally at the time. In fact, he said that every link he tried to make to Westlaw’s portal broke after a 24-hour window. Public-interest organizations ran into similar problems.

So MacWright set out to find the raw data of D.C.’s code so he could host it separately as a service in the public interest.

After making a formal request to obtain a digital version of the code in October 2012, MacWright’s inquiry eventually made it to Zvenyach’s office in January 2013. It turned out there was no publicly available digital version of the full D.C. Code’s raw data. But MacWright’s request had come at a time when the District’s government would be transitioning off its contract with Westlaw and moving to a new arrangement with LexisNexis.

That provided a window of opportunity.

Part of the agreement with Westlaw stipulated that the company needed to deliver a full digital version of the District’s law code at the conclusion of its contract. When spring 2013 came, that came in the form of an antiquated CD-ROM. But it provided Zvenyach and MacWright with what they needed to get started in transforming how the nation’s capital could access its legal code.

“Still, that [CD-ROM] … was immediately out of date,” MacWright said.

There was a lot of work to do but MacWright’s interest in open-data projects was a good fit with Zvenyach, who also likes to dabble in digital code. “You don’t find many lawyers who studied engineering in school,” MacWright said of Zvenyach, who studied mechanical engineering at the University of Wisconsin before attending law school at The George Washington University.

After some initial coding work by MacWright, Zvenyach’s office hosted a civic hackathon in April 2013. The result was DCCode.org, which is maintained by a team of volunteers, including MacWright and Zvenyach.

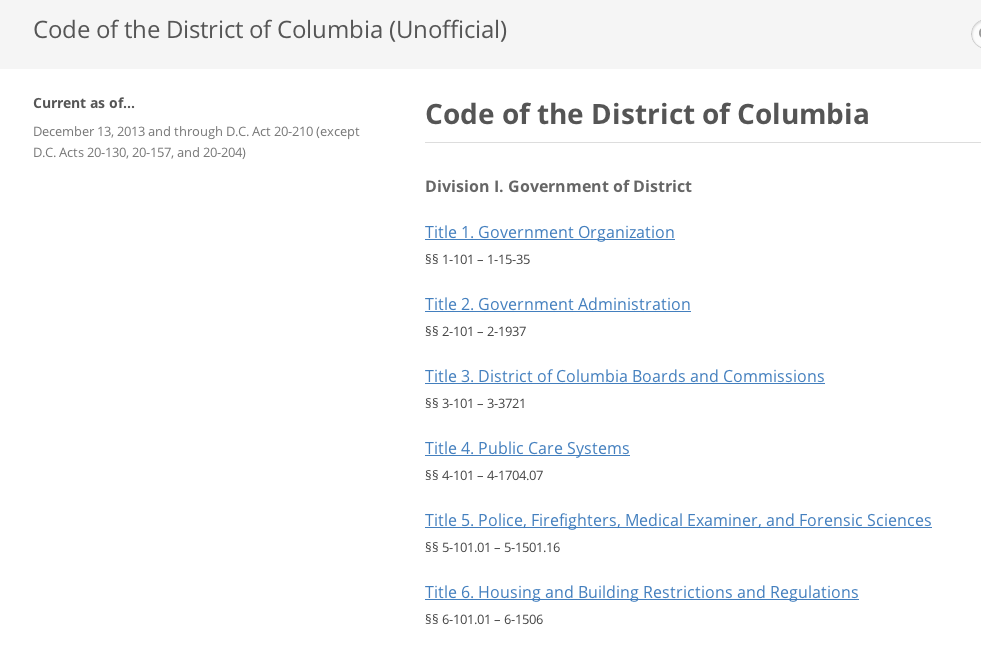

DCCode.org aims to have a simple, flexible platform to host the District of Columbia's law code.

It’s still a work in progress, MacWright said. “D.C.’s way of passing laws is so arcane… that it’s a pain” to code, noting that instructions on how to implement legislation and regulations can change, creating difficulties in crafting common technical protocols for updating the law code, accounting for amendments and other procedural items.

Eventually, MacWright and Zvenyach hope to sort out the remaining technical challenges and get the unofficial version of the D.C. Code to a point where updates can be made seemlessly.

“We’re pretty far away from having that automated,” MacWright said.

But the current product, built on an open-source platform, is highly functional and easy to navigate and search. The government of Tunisia has even used DCCode.org’s framework to host its national law code.

MacWright said there are ongoing technical challenges in dealing with the D.C. Council’s 90-day emergency and temporary legislation, which can be in effect for no longer than 225 days. That’s a product of the District’s complicated Home Rule relationship with Capitol Hill, where Congress can block the implementation of local laws in the nation’s capital within 30 days (or 60 days for certain criminal legislation) after they are enacted.

Zvenyach crafted a technical fix to deal with the uncertainty of the precise date a bill becomes a law: an application that determines a passed bill’s “effect date,” or the day it goes into effect.

“Without the eff-date, we’d be guessing when it will go into effect,” Zvenyach said.

The application came in handy recently when the D.C. government needed to determine the specific date a marijuana decriminalization measure would go into effect. (It’s July 17.)

The efforts to make the District’s law code more accessible have already improved life for those who work with the code. “It has made my job a lot easier and the jobs of my attorneys a lot easier,” said Zvenyach, who is also a member of the Uniform Law Commission.

D.C. Councilmember David Grosso remembers how difficult it was to use the D.C. Code when he worked as a council staffer from 2001 to 2007. “You couldn’t search effectively. You couldn’t copy and paste. It was absolutely awful,” he said. When Grosso won an at-large seat on the D.C. Council as an independent in 2012, he realized “it hadn’t changed that much.”

Grosso has been very supportive of Zvenyach’s work on the D.C. Code and other open-government initiatives, including The Madison Project, spearheaded by the OpenGov Foundation. Others also praise his efforts. “I wish we could clone Dave Zvenyach and transport him to every state, every county and every city around America,” said Seamus Kraft, executive director of the OpenGov Foundation.

In addition to his work unlocking the D.C. Code, Zvenyach has, separately from his duties as the D.C. Council’s general counsel, worked on two other noteworthy coding side projects: The first is an online tool called SLAPPBoomerang, a legal resource for those facing what are known as strategic lawsuits against public participation -- suits aimed at silencing critics. The second is @SCOTUS_Servo, a Twitter account that sends alerts when the the U.S. Supreme Court makes changes to its official opinions after they are handed down.

While D.C. Council Chairman Phil Mendelson — well-known in District politics for some of his old-fashioned tendencies and, like Grosso, also a former D.C. Council staffer — hasn’t necessarily championed open data, he hasn’t gotten in the way of those in his government, like Zvenyach, who want to push better open-data policies and applications.

“In the end, he didn’t need permission to do it,” Grosso said of Zvenyach.

Decoding the States

In addition to DCCode.org, a second platform hosts a different unofficial version of the D.C. Code, DCDecoded.org. That project is part of AmericaDecoded and TheStateDecoded, which are in turn elements of a larger open-source initiative backed by the OpenGov Foundation. It builds on the work of the Open Data Institute’s Jaquith to unlock Virginia’s law code.

Jaquith, who founded the state legislative bill-tracking website Richmond Sunlight in 2007, said that while “spelunking” on the state’s official file-transfer-protocol site in 2009, he stumbled across a file containing the entire Virginia state code.

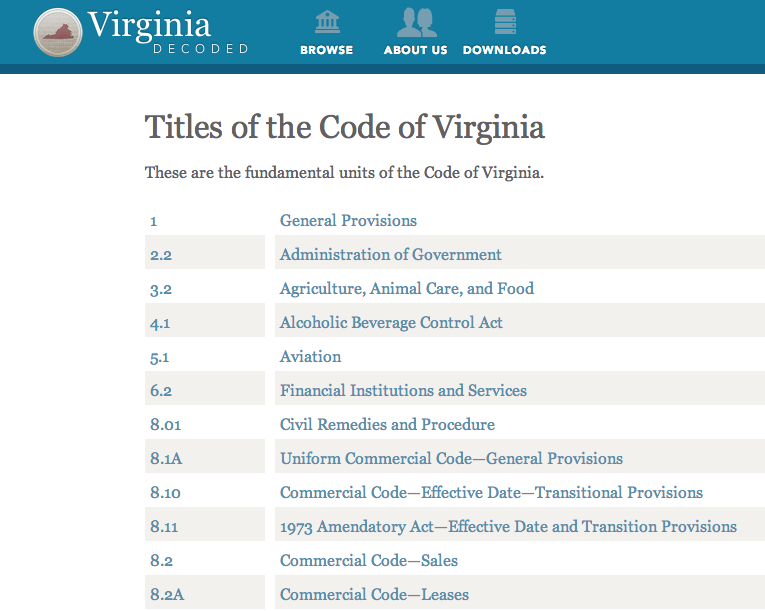

It was a golden opportunity to put the code online in a better format. After working on the project periodically, Virginia Decoded emerged, complete with hover-over definitions, references and citations.

The one factor that’s helped Jacquith on his Virginia code efforts, besides funding from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation News Challenge, has been a cooperative state government, something that open-data advocates say is rare.

Jaquith said that working with the Virginia Code Commission has been overwhelmingly positive.

“I don’t think it could have been a better experience,” he said. “They were helpful and receptive. I couldn’t have asked for a better working relationship.”

Virginia Decoded helped lay the foundation for The State Decoded project and helped the the Virginia Code Commission in its project to launch a beta version of Virginia's own new code website.

Commission employees helped beta test Virginia Decoded, provided feedback and have incorporated aspects of the site’s functionality into a beta version of the state’s own new code website, which also contains versions of the Virginia Administrative Code and the commonwealth’s Constitution.

“They’ve done everything right with it,” Jaquith said.

Jaquith said that Virginia is one of the few examples he knows of a state government being proactive on unlocking its code.

Besides Virginia Decoded and D.C. Decoded, similar beta-test sites have sprung up mostly in cities such as Baltimore, Chicago, Philadelphia and San Francisco. Miami and Raleigh are in the works, too, according to an AmericaDecoded map of code sites around the nation.

The process is more difficult at the state level because the status quo is generally more entrenched, open-government advocates argue. “I don’t really care if anyone uses my software,” Jaquith said. “But I would like to see this used as a lever to get other states to move.”

But if a handful of cities can successfully unlock their codes, it might show states the challenge isn’t as daunting as they think.

“Changing how [law codes are] produced, accessed, used and presented from a book to a website is a big change,” Kraft said. “And we recognize that … it’s a daunting and I imagine a scary problem to solve.”

The open-data proponents point to a handful of larger challenges they still need to overcome. At the top of the list is making the process of updating official law codes as technically seamless as possible.

“This is still very much in beta,” Zvenyach said, which is made abundantly clear by warnings on DCCode.org, DCDecoded.org and Jaquith’s VirginiaDecoded.org to “trust but verify.”

Then there are the security concerns in having an online law code vulnerable to hacking or malicious acts that could cause big administrative and legal headaches. But Zvenyach said it’s relatively easy to ensure there aren’t any unauthorized edits, additions or subtractions.

Over the long term, there’s the political challenge of getting the various beta-test unlocked law code sites formally recognized as an official source of a jurisdiction’s legal code.

Until a city council, state legislature or other local legislative body passes a bill that declares an unlocked digital law code as official, the only true legally recognized version will be the one that is printed in bound volumes.

“The copy that’s online should be the official version,” Jaquith said.

As more and more jurisdictions unlock their law codes, the easier — and less expensive — it should be for other jurisdictions to adapt more quickly since many technical challenges will have been ironed out.

“The more that gets done with coding, it shouldn’t cost a lot of money,” Grosso said. He has a message for his colleagues in local government everywhere: “You shouldn’t be left behind in the dark ages. … It’s not that hard.”

New York City Councilmember Ben Kallos, who chairs his city’s Governmental Operations Committee and has been an open-data leader in the nation’s largest city, said in an interview that any open-data project that makes the lives of local government officials and employees easier shouldn’t be a tough sell.

Officials “just want to see something that works,” Kallos said. “It’s easier to put it on the Internet and let other people do the heavy lifting to make government information more accessible and usable.” He has been actively pushing an open-data and transparency legislative package in the New York City Council.

Kallos, like Zvenyach, has been a member of the small coalition of open-government advocates and local officials in five cities — Boston, Chicago, New York City, San Francisco and Washington, D.C. — that has been working for months on parallel open-data efforts. They plan to issue a joint declaration later this month that challenges jurisdictions across the country to make a commitment to unlock their data for the public's benefit and create user-friendly and accessible digital platforms to host government information.

Building upon the work already done in these open-data cities, the organizers and coalition partners hope their efforts will lead to a common digital platform that jurisdictions can use to host local government information.

In the end, the idea is to create a more open society and break barriers between citizens and their local governments.

“Ultimately, its the residents who come up with the best ideas and provide the best feedback,” said San Francisco Supervisor Mark Farrell, a former venture capital executive and attorney who has been a leader in his city pushing open-data initiatives. “Sometimes, feedback doesn’t get back to us at City Hall.”

But that’s all changing, Kallos said. “The agility of code is pushing government to be more responsive.”

WATCH: New York City Councilmember Ben Kallos at a Personal Democracy Forum Open Government workshop