Connecting state and local government leaders

While green spaces are often linked to gentrification, new research shows certain types and characteristics of urban parks play a much greater role than others.

There is no hotter hot-button issue among urbanists than gentrification. It’s a subject we cover often at CityLab, busting myths and misconceptions about what drives it, where it occurs, and its effects on people and neighborhoods (which can be more positive, even for lower-income residents, than commonly thought).

Most urbanists and economists have long thought that gentrification is driven, in large part, by the desire of more affluent and educated people to reduce their commutes and be close to the offices and workplaces of the central business district (that’s why the term is often used synonymously with the back-to-the-city movement).

But it is becoming increasingly apparent that more is at work. Gentrification is also driven by a desire to be close to unique urban amenities like restaurants, galleries, museums, or even fitness facilities. In some cities, gentrification is associated less with proximity to the workplaces of the central business district and more with the desire to access the amenities and park spaces of what has been dubbed the central recreational district. The pricey condo and office towers that line New York’s High Line park stand as physical exemplars of just this.

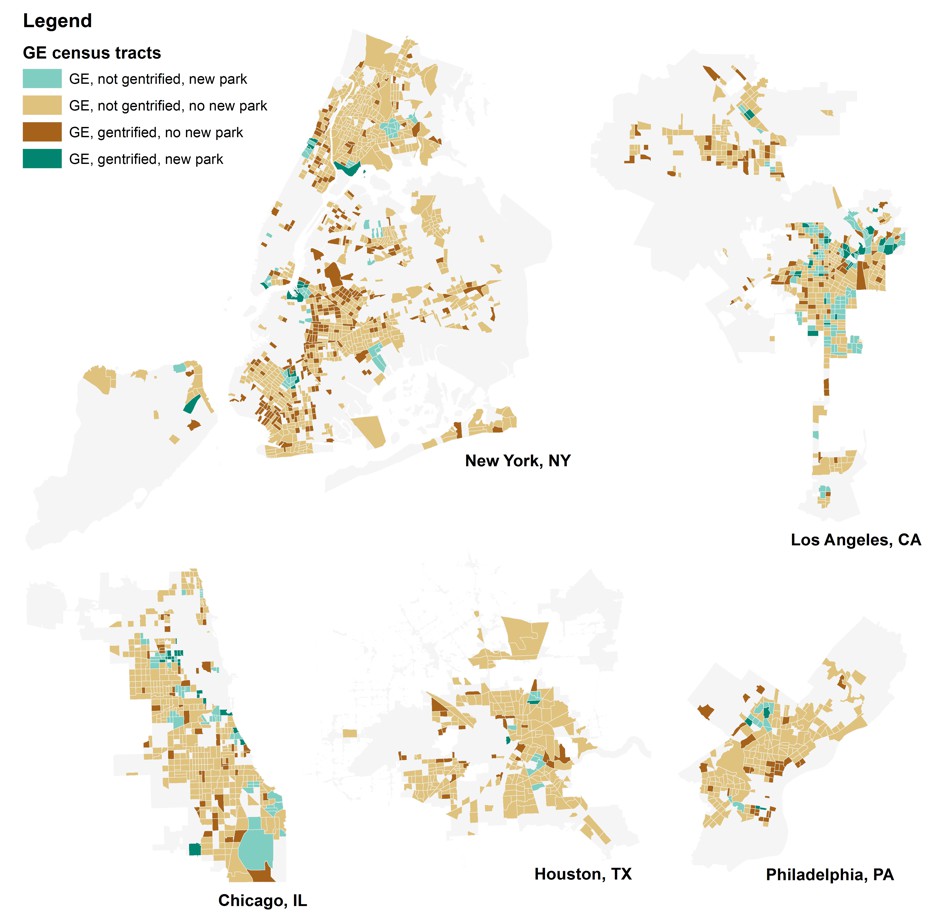

Locations of gentrification-eligible (GE) tracts in 2008 and gentrified tracts between 2008 and 2016 for five of the largest cities in the U.S.

Now, a study by Alessandro Rigolon of the University of Utah and Jeremy Németh of the University of Colorado takes a close look at the role of urban parks and green spaces in gentrification. Published in the journal Urban Studies, their research unpacks the roles of several elements of parks in gentrification.

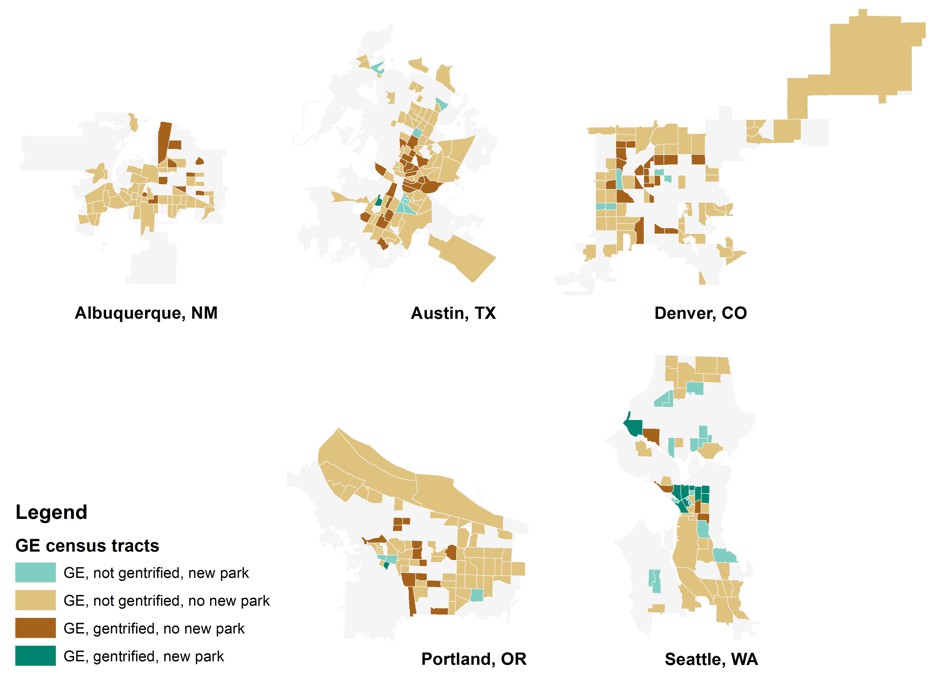

The study covers 10 cities (not metros) in different regions of the country. This group includes five of the very biggest cities—New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Houston, and Philadelphia—and five somewhat smaller cities that have also seen significant gentrification: Seattle, Denver, Austin, Albuquerque, and Portland, Oregon. It tracks the role of parks in the gentrification of the cities over 15 years, from 2000 to 2015, a period during which the back-to-the city movement accelerated gentrification. It breaks this longer time frame into two shorter periods—2000-2008, before the crisis, and 2008-2015, after the crisis, when gentrification took off even more.

The study pegs gentrifying neighborhoods in these cities with a fairly standard definition that tracks changes in median income, housing values and rents, and college graduates. The authors dub neighborhoods or census tracts that start out with median incomes lower than that of the city as “gentrification-eligible.” Under this definition, about half the tracts in these cities were gentrification-eligible in the year 2000 (ranging from 43 percent in Seattle to 56 percent in Chicago). About a tenth to more than a quarter of these gentrification-eligible neighborhoods actually gentrified, depending on the city, from a low of 12 percent in Houston to a high of 27 percent in Denver.

The study goes beneath parks as a broad category and focuses on several key characteristics of parks and their effect on gentrification. These are: size, overall quality, whether they are new, proximity to downtown, and whether or not they are linear “greenway parks,” longer than a mile, that include an active transportation component like bike lanes.

More new parks (381) were built in the earlier pre-crisis period than in the later post-crisis period (215), likely due to the impact of the Great Recession on local park finances. To test propositions about the role of parks in gentrification, the study develops a series of advanced statistical models which also control for factors including income, density, race, housing, proximity to downtown, and accessibility to transit, among others.

Locations of gentrification-eligible (GE) tracts in 2008 and gentrified tracts between 2008 and 2016 for five medium-sized cities in the U.S.

The upshot of the study is that it is not parks or green space per se that spur gentrification: Certain types and characteristics of parks play a much greater role than others.

The first big finding is that long greenway parks, like the High Line or Atlanta’s BeltLine, are the biggest culprits in gentrification. According to the study, being located within a half-mile of a new greenway park increases the odds that a neighborhood will gentrify by more than 200 percent (their actual estimates range from 222 to 236 percent). Five of seven new greenway parks in the study spurred significant gentrification in their surrounding neighborhoods, including New York’s High Line, Chicago’s 606 trail, and Houston’s Buffalo Bayou Park.

The reason for this is likely the simple fact that long linear greenway parks provide ample opportunities for new real estate development along their lines. The study also finds that greenway parks were much more likely to spur gentrification in the latter 2008-2016 period, but not in the 2000-2008 period. There are likely two reasons for this. On the one hand, as the study notes, even though fewer parks opened during this latter period, it is the time during which many of the most well-known greenway parks like the High Line and the 606 trail opened.

Second, parks located closer to downtown also play a larger role in gentrification (though not as big as greenway parks), increasing the odds that a neighborhood will gentrify by about 90 percent. Here the study points out that for every one-mile increase in distance from downtown, the odds of gentrification for a gentrification-eligible neighborhood decline by about 20 percent. This effect was especially large in downtown L.A., in particular along the Los Angeles River, and also in Seattle and New York City.

A couple of things matter considerably less. For all the fuss made about big parks driving gentrification, the variable for park size fails to show statistical significance with gentrification. In other words, there is no evidence that larger parks are bigger drivers of gentrification than scattered smaller parks. Parks of any size trigger gentrification when they are located close to downtown.

Furthermore, it is the very existence of parks and not their quality that is bound up with gentrification. In fact, the study finds that there is less gentrification on balance in cities with higher-quality park systems.

Ultimately, gentrification is tied to the particular location, type, and function of urban green spaces. Linear greenway parks and parks located close to downtown are most closely tied to gentrification; these are also the parks that are most closely tied to the creation of central recreational districts, another key driver of recent gentrification.

This has a couple of useful implications for mayors, urbanists, park planners, community developers, and neighborhood groups concerned with managing the gentrifying effects of parks and green space. The authors suggest that cities steer a good chunk of park development to building and refurbishing parks and green space, including large parks, in less advantaged areas outside the downtown core.

They write: “[A]s we find that large parks do not foster gentrification more than small parks, planners and policymakers should strive to address deep rooted inequities in accessible park acreage by adding substantial amounts of new green space in park-poor, low-income communities of color, while also providing and protecting nearby affordable housing.”

On the other hand, cities should make concerted efforts to proactively address gentrification around new greenway parks and downtown adjacent parks. This can include policies and provisions for more affordable housing in neighborhoods surrounding these parks and efforts to create employment for less advantaged residents in the parks, or in developments that appear alongside them. Or, for developers who take advantage of the park amenities, cities could assess fees or taxes that can be used for affordable housing and neighborhood development, or mandate that the developers set aside a percentage of their units, say 20, 25, or even 30 percent, for affordable housing.

Great parks and open spaces help to make great cities. They provide areas for recreation and burning off the stresses and strains of everyday urban life, and their tree canopy helps communities mitigate pollution. People feel more attached to their cities and their neighborhoods when they can access nature, and green space contributes to the physical beauty of their neighborhoods.

Parks are a central piece of the civic infrastructure that helps bring people and families together in large, anonymous cities. What cities need to do is ensure that their initiatives for parks and green space are fully integrated with their broader strategies for more inclusive development for all neighborhoods and residents.

Richard Florida is a co-founder and editor at large of CityLab and a senior editor at The Atlantic.

NEXT STORY: Restore Pell Grant Eligibility to Incarcerated Students