LOS ANGELES—California is ascendant and its governor, Gavin Newsom, knows it. His state is having dramatic success in containing the coronavirus pandemic, and Newsom is so bullish about its status that he talks about California as if it were one of the world’s most powerful nations, not merely the largest state.

“I hope we’re modeling good behavior,” Newsom told me the other day, when I caught up with him by phone from Sacramento, as he was planning a multistate response to the crisis with his fellow Democratic governors in Oregon and Washington State. “Look, we’re the fifth largest economy in the world, 40 million strong, we’re as diverse a state as exists in this country, [with] 20-some percent of the state foreign-born.” In other words, California amounts to a kind of country unto itself, and is just responding accordingly.

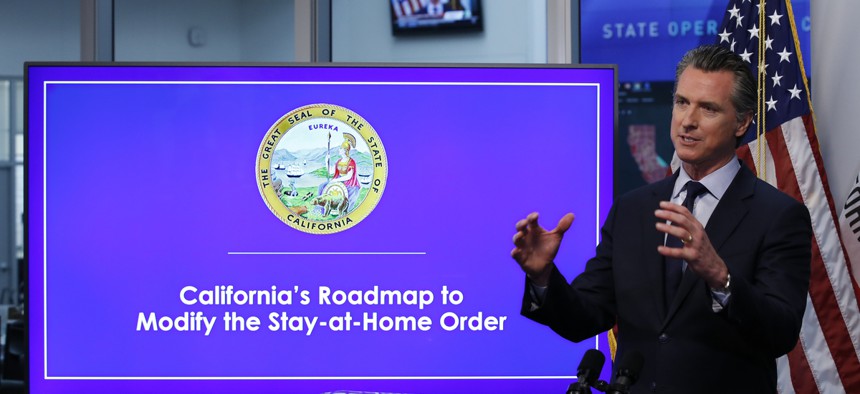

This month, Newsom, whose March 19 mandatory stay-at-home order was the first in the country, invoked California’s power as a “nation-state” to announce that it would lend 500 state-owned ventilators to other COVID-19 hot spots in need, and would use its immense budget surplus to start an almost $1 billion supply chain from China to import 200 million respiratory and surgical masks.

Newsom’s moves—and those of other blue-state governors who have taken the lead in confronting the crisis in the face of the Trump administration’s failures—are the sort of decisive action that Americans might have more readily expected from the federal government. From the Pacific Rim to the Northeast, the blue states have leapt early into the breach with strong measures on social distancing, determination to ramp up testing, and carefully considered plans for returning to some semblance of a normal in calibrated phases. The White House has been forced to play catch-up.

Newsom’s approach is also the clearest sign yet that California’s exceptionalism—its longtime self-image as the place that imagines how the future will look and work, for aerospace and computing and entertainment—may well be the new American exceptionalism. How the state responds to this massive economic, social, and health-care challenge could prove that self-image accurate—or shatter it entirely.

Overall, California appears to have succeeded in sharply limiting the spread of the virus, though the state remains substantially under-tested, so the statistics may not be as encouraging as they seem. As of yesterday, 31,675 cases had been confirmed statewide, and 1,178 deaths—compared with 247,512 cases and 14,347 deaths in New York State.

Newsom’s acting so unilaterally, in opposition to Washington, does hold some risks. California taxpayers remit about 15 percent of individual contributions to the U.S. Treasury, yet California is, in the end, only a state, responsible to and dependent on federal laws and largesse like any other. It can buy equipment, and influence world markets, but it can’t set national trade or economic policy. But it’s easy enough to imagine a red state charting a comparably independent course against a future Democratic administration in Washington—one that the liberals who are applauding Newsom today might oppose.

Still, Newsom has so far won widespread praise, not only for his response to the virus crisis, but for his articulation of an alternative vision to Donald Trump and the Republicans’ approach to government, on issues including auto emissions and air pollution, homelessness and health care.

Last week, Newsom and his fellow Democratic governors, Kate Brown of Oregon and Jay Inslee of Washington—like six of their East Coast counterparts—announced that they would collaborate on a joint blueprint for reopening their states’ economies, one that would outline clear medical and scientific indicators for when it be safe to begin a gradual return to more normal life. They pledged a particular effort to protect vulnerable populations in places such as nursing homes, and to create a system to test, track, and isolate COVID-19 patients even after the broader restrictions are lifted.

A day later, Newsom outlined the half-dozen criteria he will use in deciding when and how to lift his now indefinite stay-at-home order, including the availability of widespread testing and tracing, the creation of new guidelines for schools and businesses, and assurances that nursing homes and other group-care settings can be safe and hospitals are prepared for a potential surge in patients. He warned that Californians should expect to continue wearing masks in public, and to eat in restaurants with fewer tables, where servers wear gloves and masks, as well as prepare for the unlikelihood that sporting events, concerts, and festivals would resume by summer. And he appointed an advisory council, led by the former Democratic presidential candidate Tom Steyer and including all of the state’s living former governors, to oversee the restarting of the economy.

California’s seeming success has been a kind of personal vindication for Newsom, who won office in 2018 after serving as lieutenant governor to the hyper-competent, politically adroit Jerry Brown. There was some initial skepticism about whether Newsom would be up to the top job. He cuts a coiffed, telegenic figure, and as mayor of San Francisco more than a decade ago, while in the midst of a divorce, had a sexual relationship with an office subordinate, which was later made public. He acknowledged an alcohol problem, for which he sought counseling. He resumed moderate drinking a couple of years later.

Newsom is intimately familiar with the day-to-day domestic realities of isolation. He and his wife, Jennifer Siebel Newsom, a documentary filmmaker and actor, have four young children at home. “That’s the most intense part,” he said. “Our school days, probably, honestly last an hour, because they’re just not modeling the counsel of their parents. And so that’s the hardest part, not being able to see their friends and have playdates. Zoom only worked for a week or two before they were just over the virtual playdate.”

He has a considered analysis of why California seems to have been singularly prepared to meet the threat of the virus. “This narrative of punching above our weight, this narrative around being a nation-state—that narrative is a big part of the California spirit, of being dreamers and doers, this entrepreneurialism that the future happens here first,” he said. “There’s a pride in that; there’s perhaps an arrogance at times.” But, he added, “I think all of that is built into the DNA, and is all part of the sauce at the moment.”

California’s DNA has long made it a research pioneer in fields such as astronomy and nuclear physics and medicine and genetics. Public-health officials in Santa Clara County, in the heart of Silicon Valley, established an incident command center, to plan for handling the virus, three days after the first confirmed U.S. case. In mid-March, when the virus’s broad spread was becoming apparent, scientists at Berkeley’s Innovative Genomics Institute raced to develop a rapid test, which has since been successfully deployed to residents around the state. Bloom Energy, a company based in Sunnyvale that normally produces fuel-cell power generators, heeded Newsom’s call to rehabilitate scores of damaged ventilators in the state’s inventory. More broadly, the move to virtual workplaces around the country has helped spawn thousands of new tech jobs here.

The Golden State’s perpetual susceptibility to imminent disaster has also helped prepare it to meet this one, Newsom said. California’s political and governmental infrastructure is conditioned to confront earthquakes, wildfires, mudslides, drought, floods, and every other manner of pestilence, natural and man-made—and largely in a way that ignores partisan politics. “We sort of transcend during times of crisis,” Newsom said. “And you look at what the state’s been through in 2015, with the fires, and in ’17 and ’18 and last year—not only the combination of wildfires but the blackouts that really reinforced those relationships … and I think that, perhaps more than anything else, has really proven to be key in this moment.”

That’s not to say political pushback has been nonexistent. One challenge is that Newsom has to manage a political and demographic constituency as diverse as the nation’s, and almost as divided. Representative Devin Nunes, a fervent Trump ally from the Central Valley, harshly criticized social distancing and school closures as overkill. And Newsom faced criticism from some fellow Democrats for issuing his statewide stay-at-home order only after the mayors of the state’s two principal cities—London Breed in San Francisco and Eric Garcetti in Los Angeles—had already done the same. One of Newsom’s aides told me the governor had wanted localities to take the lead in social-distancing measures, to ensure broad buy-in when he took statewide action.

Unlike officials in some other states, Newsom has largely avoided vocal public criticism of the Trump administration, partly because large swaths of inland and rural California are as politically red as it gets. For much of the past half century, national conservatives have scorned California as a dystopian failed state of chronic problems and social permissiveness. Despite the state’s severe homelessness crisis and yawning gap between wealth and poverty, that kind of caricature no longer cuts as much ice with respect to the state that has given the world Apple and Tesla and Netflix. Still, the conservative residents of central and inland California could not be more politically different from their liberal counterparts on the coast. “About 40 percent of the state is more likely to listen to Trump than to him,” the Newsom aide told me, speaking on condition of anonymity in order to be candid. “Part of his rhetoric was not alienating those folks—knowing that they would have to take real sacrifice—in order to build trust with that part of the state, so that they would pay attention to him when it came time to take mandatory action.”

Newsom told me that he attributes part of the state’s early awareness of the threat’s gravity to its acceptance, beginning in late January, of flights of Americans returning from China, many of whom were then quarantined at military bases. “A number of states, as you recall, were not interested in taking those repatriated flights from China,” he said. “And as a consequence, we started to have those direct conversations, not only at the White House, but at CDC and HHS, and that really allowed us to develop a two-way line of communication.”

Forty years ago, another onetime California governor rode to the White House on his critique of Washington’s failures, and his own pledge to restore American greatness. Newsom’s politics are a world away from Ronald Reagan’s, but he is a fifth-generation Californian, and he said he feels a singular responsibility for preserving and upholding his home state’s reputation. “It’s an extraordinary legacy, this state,” he said. “It’s always an unfair comparison, but people talk in terms of east-west, where out here in the west, people come to start something, whereas out there in the east, they come to join something. So there really is that pioneering spirit of always looking into the future, and looking out over that coast—the coast of dreams, which Ronald Reagan used to speak to.”

Reagan came galloping out of California to win the presidency in the face of Jimmy Carter’s failures of management and competency, and amid widespread public distrust of Washington in the aftermath of Vietnam and Watergate. The COVID-19 crisis may well become a comparably defining moment in American politics, one that the 52-year-old Newsom is well poised to exploit, if his state’s handling of it turns out better than so many other places’ in the end. Newsom told me he’s grateful for California’s seeming “early success of bending the curve” of the pandemic. But, he acknowledged, “By no stretch do I feel that we are on the other side of it.”

He also knows firsthand the plight of the state’s small businesses, so many of which he has ordered closed. Newsom made his fortune through a series of investments in wineries, hotels, restaurants, and other hospitality businesses, beginning with his first PlumpJack wine store, which opened in San Francisco in 1992. He noted that his own businesses “may be in a blind trust, but they’re also boarded up right now, and the impacts are profound and pronounced.”

He has pegged the cost of the state’s initial virus response at $7 billion and counting, and so far, it has managed to finance its actions out of the large budget surplus built up over the tenure of his predecessor Brown. “The reserves are there, and they’re obviously incredibly important,” he said. “I think the greatest struggle we all have is the unknown,” he added. He noted that next year’s projected state budget—due out soon—will be grim. “I can just say this: We are modeling over the next three years some jaw-dropping deficits that we’ll be making public, and unemployment rates the likes of which we’ve never seen in our lifetime. The economic picture is not rosy, and incredibly sobering … We’re dealing with a novel virus. And while we believe certain things to be true, we have to recognize the fragility of those beliefs in the context of how this virus may act.”