Connecting state and local government leaders

A rise in injection drug use is fueling a spike in hepatitis C among young opioid and heroin users.

This article was originally published at Stateline, an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts, and was written by Christine Vestal.

In an unrelenting opioid epidemic, hepatitis C is infecting tens of thousands of mostly young, white injection drug users, with the highest prevalence in the same Appalachian, Midwestern and New England states that are seeing the steepest overdose death rates.

Like the opioid epidemic that is driving it, the rate of new hepatitis C cases has spiked in the last five years. After declining for two decades, new hepatitis C cases shot to an estimated 34,000 in 2015, nearly triple the number in 2010, according to a recent report from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

With better screening for the bloodborne disease and more treatment using costly but highly effective new drugs, hepatitis C could be eradicated, according to a new study from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

But epidemiologists agree that without quelling the opioid epidemic, or ensuring that nearly all injection drug users have access to sterile needles, hepatitis C will continue to spread. It already affects 3.5 million Americans who, if not treated, could die of liver cirrhosis or cancer. At an average cost of $30,000 per person, the tab for treating everyone with the disease would exceed $100 billion.

“We have two public health problems that are related — it’s called a syndemic — and we can’t address one without addressing the other,” said James Galbraith, an emergency room physician at the University of Alabama at Birmingham Hospital.

To reduce new hepatitis C infections, he said, states need to provide clean syringes for injection drug users who otherwise have no other contact with the health care system than emergency departments and jails.

But advocates for syringe exchanges say the prospect of standing up enough clean needle programs in the nation’s hardest hit communities to stem the spread of hepatitis C is daunting.

Unlike the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s and previous drug epidemics, which were spawned and defeated in urban settings, this opioid epidemic is ensnaring people who live in far-flung small cities and rural communities with few public health resources and scant political will to provide sterile needles to illicit drug users.

Nevertheless, there is “more momentum towards establishing syringe programs now than at any time in the past 20 years,” said Daniel Raymond, policy director of the Harm Reduction Coalition, which advocates for syringe exchanges.

A new wave of syringe exchange laws has cropped up, even in some Republican-led states that previously opposed them. Since 2015, Florida, Indiana, Kentucky, Louisiana, Montana, New Hampshire, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Tennessee, Utah, Virginia and West Virginia have all enacted syringe exchange laws.

“But it’s a bit of a race against the clock,” Raymond said. “Can we stand up enough new programs in time to blunt the rise in hepatitis C? I’m optimistic but under no illusions. There’s a lot of work to do to build political will for this.”

For states that have taken this step, the next hurdle will be getting local officials to agree to set them up, Raymond said. Kentucky and North Carolina have moved quickly to launch exchanges in several hard hit counties. But other states are still struggling with local opposition from people who say that providing free supplies to drug users only enables them to continue doing what they’re doing.

A Quiet Disease

Compounding the problem is a lack of perceived urgency. Hepatitis C doesn’t kill children or adults in the prime of life. Most people infected with the virus experience no symptoms and the serious liver damage it can cause doesn’t show up for 20 to 40 years after someone is infected.

“HIV is a dreaded disease,” said Brian Strom, who chaired the committee that wrote the National Academies of Sciences study. “Hepatitis isn’t and it should be.”

“It is ignored largely because of a perception that it is tied to drug use and not a threat to the general public,” he said. “The irony is that now that people are starting to worry about drug users because they’re entering the mainstream population, it’s going to help hepatitis get the attention it deserves.”

In Scott County, Indiana, it took an outbreak of HIV in 2015 to motivate then-Gov. Mike Pence to declare a public health emergency and allow a syringe exchange program to be established in the community.

Nearly three years before the outbreak, public health officials were seeing a sharp increase in hepatitis C, and hospitals were reporting increasing numbers of overdose cases, as well as endocarditis (heart infection) and skin abscesses, all signs of injection drug use.

Searching for answers, Indiana public health officials at the time sought advice from a small community in central New York that had quelled a hepatitis C outbreak by establishing a syringe exchange. But doing the same thing in Republican-led Indiana was a non-starter.

Primarily a response to the AIDS epidemic, syringe exchange programs were first established in the U.S. in the mid-1980s as largely underground operations, since most state laws prohibited them. A ban on federal funding of syringe exchanges wasn’t lifted until last year. Today there are nearly 200 programs, clustered mainly in major coastal cities.

But to stanch the recent spread of hepatitis C, a new study funded by the CDC estimates the nation needs at least 2,200 more programs located in the mainly rural areas where young drug users are contracting the disease.

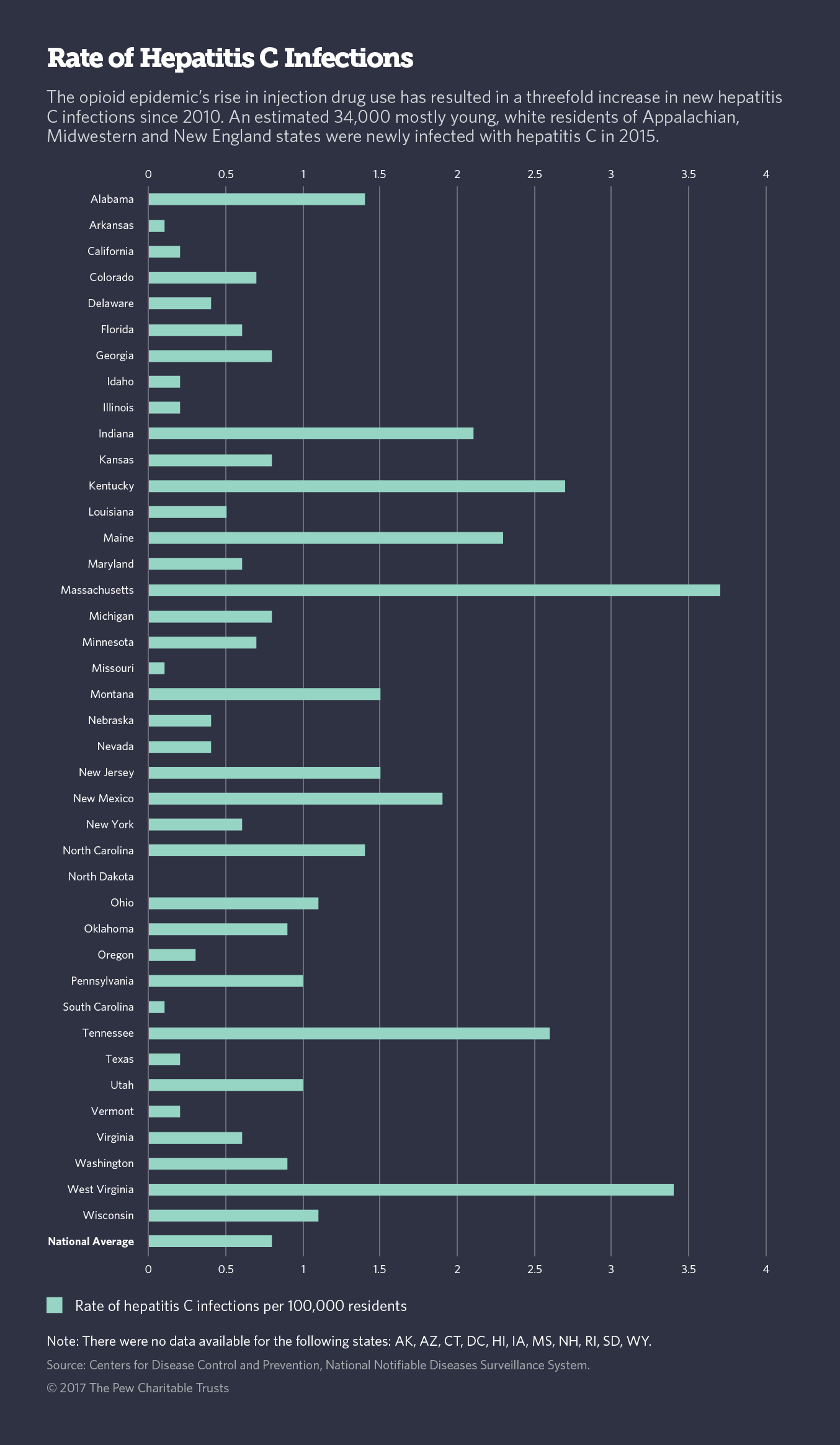

According to CDC data, Indiana, Kentucky, Maine, Massachusetts, New Mexico, Tennessee and West Virginia have hepatitis C infection rates that are at least double the national average. And Alabama, Montana, New Jersey, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Utah, Washington and Wisconsin have rates that are higher than the national average.

In addition to syringe exchanges, states need to adopt policies aimed at testing more people at risk for hepatitis C and treating more of those living with the virus, said John Ward, director of the CDC’s viral hepatitis program.

More Testing

Hepatitis C primarily affects injection drug users and members of the baby boomer generation born between 1945 and 1965, when the viral disease is believed to have been transmitted through the health care system before infection control and other precautions were widely adopted.

Testing for the viral infection is spotty. Alaska, Arizona, Connecticut, Hawaii, Iowa, Mississippi, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, South Dakota, Wyoming and the District of Columbia do not consistently report data on hepatitis C to the CDC. Nationwide, tests for the contagious disease are performed so infrequently that the CDC multiplies reported cases by a factor of 14 to estimate the real number of infections.

In a few major urban centers where injection drug use has been prevalent for decades, hospital emergency departments have expanded the scope of their hepatitis C testing.

Until the opioid epidemic started exploding in the Appalachian region of north Alabama, the University of Alabama at Birmingham Hospital wasn’t one of those places.

But in 2015, after droves of people started coming into the emergency department for treatment of drug overdoses, heart valve infections and skin lesions, Galbraith decided to stop asking people whether they were drug users. Instead, he directed his staff to simply tell patients they were going to run a hepatitis C test on their blood unless they objected. Only 15 percent opted out.

What Galbraith found was that 11 percent of baby boomers tested positive for hepatitis C and 7.4 percent of people born after 1965 tested positive, rates that were far above the national average.

Most surprising, Galbraith said, was that 14 percent of young white patients tested positive for hepatitis C — nearly 18 times the national average — while only 3 percent of young black patients tested positive.

He cautioned that the high rates he found in the emergency department do not represent the general population of the Birmingham area because patients who come to emergency departments for care are disproportionately poor and uninsured.

After mapping the residences of the 1,200 young patients who tested positive for hepatitis C in the last two years, Galbraith found that most lived in rural areas of two nearby counties where heavy injection drug use was suspected based on county overdose deaths and hospital admissions data.

In follow-up interviews, he found that the majority of patients who tested positive self-identified as past or present injection drug users, although he estimates that the real rate is closer to 90 percent.

Galbraith used the data to try to convince Alabama lawmakers to approve a bill that would create syringe exchanges in counties with the greatest risk of spreading hepatitis C. It was unanimously approved in the House, but failed to pass the state Senate before time ran out this year. He and other public health advocates intend to try again next year.

NEXT STORY: Houston Also Had a Disastrous 'Once-in-500-Year' Flood in 2001