Connecting state and local government leaders

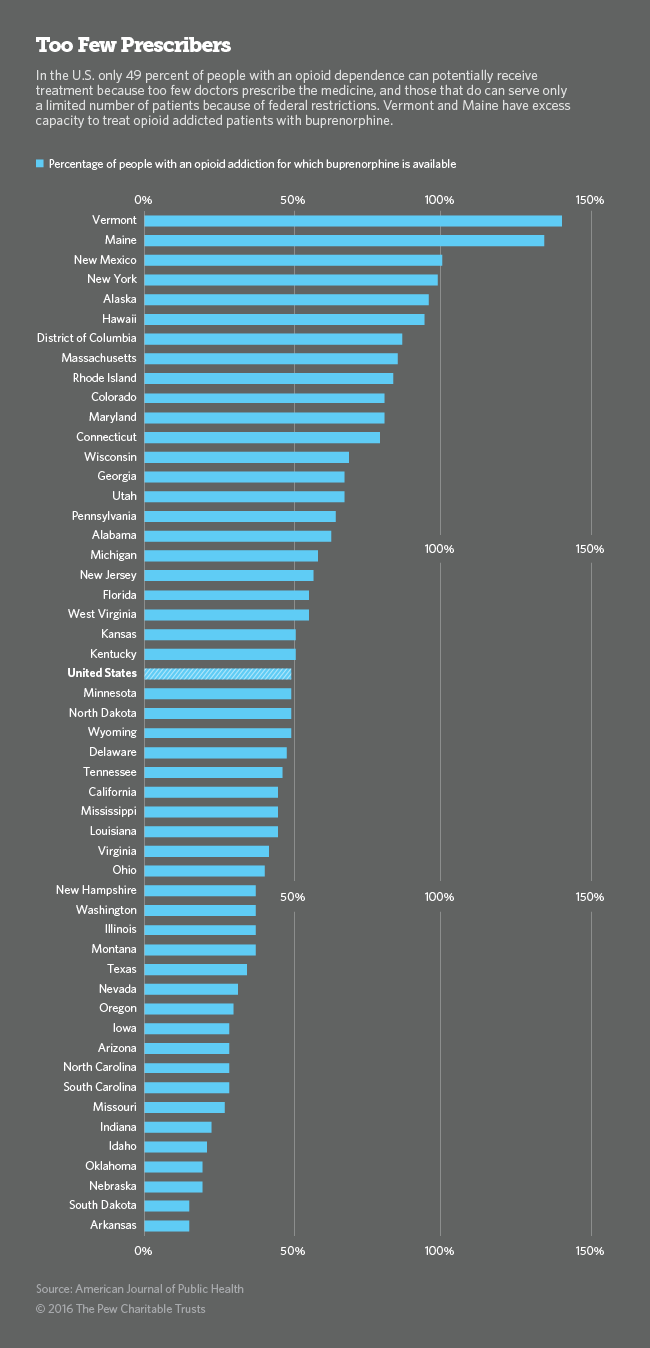

More than 900,000 U.S. physicians are allowed to write prescriptions for painkillers such as OxyContin, Percocet and Vicodin. But fewer than 32,000 doctors can prescribe a medication, buprenorphine, which could help many Americans beat their addictions to those drugs.

This story originally appeared on Stateline, an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts, and is part of a three-part series, DEADLY BIAS: Why Medication Isn’t Reaching the Addicts Who Need It. Part III was written by Christine Vestal.

SAN FRANCISCO — Dr. Kelly Eagen witnesses the ravages of drug abuse every day. As a primary care physician at a public health clinic here in the Tenderloin, she sees many of the city’s most vulnerable residents.

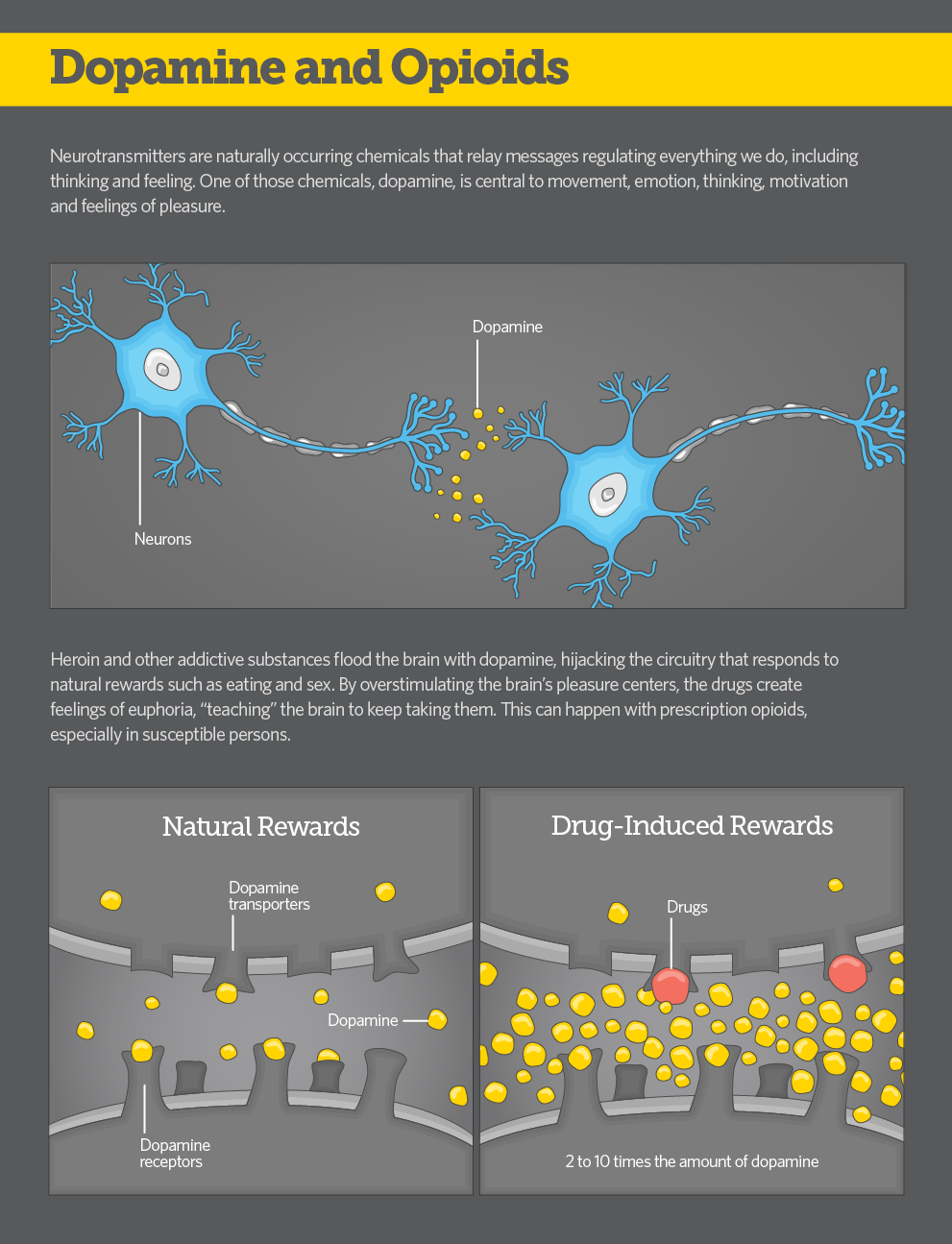

Most are homeless. Many suffer from mental illness or are substance abusers. For those addicted to opioid painkillers or heroin, buprenorphine is a lifesaver, Eagen said. By eliminating physical withdrawal symptoms and obsessive drug cravings, it allows her patients to pull their lives together and learn how to live without drugs.

Clinical studies show that U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved opioid addiction medicines like buprenorphine offer a far greater chance of recovery than treatments that don’t involve medication, including 12-step programs and residential stays.

But as the country’s opioid epidemic kills more and more Americans, some of the hardest-hit communities across the country don’t have enough doctors who are able—or willing—to supply those medications to the growing number of addicts who need them.

More than 900,000 U.S. physicians can write prescriptions for painkillers such as OxyContin, Percocet and Vicodin. But because of a federal law, fewer than 32,000 doctors are authorized to prescribe buprenorphine to people who become addicted to those and other opioids. Most doctors with a license to prescribe buprenorphine seldom—if ever—use it.

Buprenorphine is the primary addiction treatment tool for Eagen and the seven other staff physicians at the Tom Waddell Urban Health Clinic.

Getting patients started on the medication can be time-consuming. When they’re too busy with other patients, they rely on a small medical team at a county-funded center in the nearby Mission District to screen patients and, if the medication is appropriate for them, determine the correct dose.

At this central “induction center” on Howard Street, a half-time doctor, two nurse practitioners, a behavioral health counselor and two administrators have been providing screening and initial care for low-income opioid and heroin addicts since 2003.

Eagen said working with the Howard Street team makes her life easier. “When the patient is handed back to me, I know that the person is not at risk for imminent relapse. They’re the easiest patients I have.”

Unrealized Potential

With its long history of providing drug treatment and free health care to uninsured residents, San Francisco is particularly well-equipped to battle the opioid and heroin epidemic. But even here, federal prescribing restrictions and lack of information keeps many doctors from entering the fray.

When the National Institute on Drug Abuse funded the research that led to buprenorphine’s development more than a decade ago, it hoped that office-based prescribing of buprenorphine, which comes in a soft tablet and dissolvable film, would mean greater access to addiction medication nationwide.

It hasn’t happened. Most doctors claim they don’t have the training or the time to treat high-maintenance opioid addicts in their busy practices, despite urgent calls from federal and state officials. “I really think doctors are scared of prescribing it,” Eagen said. “They worry they’re going to make people sick when they start taking it.”

But an increasing number of physicians are starting to push for greater use of buprenorphine.

“We doctors are the ones who caused this epidemic by overprescribing pain medications. We need to get more involved in fixing it,” said Kelly Pfeifer, a physician with the California HealthCare Foundation, which advocates for greater availability of addiction treatment and prevention.

Nationwide, about 21.5 million people 12 and older, or 8 percent, had some kind of substance use disorder in the past year, according to a national survey by the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Of those, almost one in 10 were hooked on painkillers — 1.9 million — and more than half a million were hooked on heroin. And those numbers are rising. Among the low-income adult population served by Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act, the rate is much higher: An estimated 13 percent of newly eligible Medicaid enrollees suffer from addiction.

In California, which was among the first states to expand Medicaid, as many as 370,000, of the 2.9 million people newly eligible for Medicaid, may be in need of treatment.

Under a first-of-its-kind agreement with the federal government, California’s county-run Medicaid programs are slated to begin covering a full set of addiction treatment options recommended by the American Society of Addiction Medicine, including opioid addiction medications. San Francisco County and the rest of the Bay Area will be the first to roll out the new drug treatment benefits later this year.

Federal Rules

Three medications have been approved to treat opioid and heroin addiction. Methadone, a long-acting opioid that fulfills the addicted brain’s perceived need for heroin, was approved for treatment in 1964 and is dispensed at highly regulated clinics scattered around the country, mostly in urban areas.

Patients must visit the clinics daily to swallow a liquid dose of methadone under supervision of a certified health professional. For many, that means traveling substantial distances early in the morning before work. Some patients can qualify for take-home doses for use on weekends.

Naltrexone, a daily pill approved in 1984 for heroin addiction, can also be prescribed by a doctor. But until 2010, when naltrexone was introduced in injectable form, as Vivitrol, it was considered much less effective than either methadone or buprenorphine at keeping people in recovery from heroin addiction.

Buprenorphine, approved in 2002, is prescribed by doctors in an office setting, making it much more convenient than methadone. Patients simply pick up a monthly supply of the medication and take it on their own. Like methadone, it is a long-acting opioid that relieves drug cravings and physical withdrawal symptoms with fewer of the side effects of other opioids.

In anticipation of buprenorphine’s approval, a 2000 federal law required doctors to seek a special license from the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration to prescribe it. The federal law requires eight hours of training and limits the number of patients per doctor to 30 in the first year and 100 in subsequent years. That limit was established to prevent “pill mills,” in which doctors prescribe the medication for a fee without ensuring that patients are actually using the pills to stay in recovery from a drug addiction.

Although the vast majority of doctors with a buprenorphine license see only a few patients, the federal limit prevents some doctors in high-demand communities and urban neighborhoods from providing care to everyone in need.

In response to the worsening heroin and opioid epidemic, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services is considering an increase in the patient limit for prescribing buprenorphine. Advocates for greater availability of addiction medicines argue HHS should go further, eliminating the cap altogether and allowing nurses and physician assistants to prescribe the medication.

But the federal government argues that without adequate record keeping and physician oversight, too many patients could end up selling the medication on the street.

Although buprenorphine does not produce the euphoric effects of heroin, many drug users purchase it to tide themselves over until they can score the real thing. Doctors who advocate for greater use of buprenorphine argue that the threat of diversion is minor compared to the lifesaving potential of the drug.

'Summer of Love'

Buprenorphine doesn’t just save lives by fighting addiction, advocates say. It also connects drug addicts to mainstream medical care and can help improve their health, which drug users typically neglect.

Dr. David Smith, a San Francisco physician credited with starting the first free health clinic in the country, in 1967, argues that in the long run, patients are better off in the care of physicians than addiction treatment providers, such as counselors and therapists, without medical training.

“We’re finding that when people with addictions start going to a primary care doctor, their physical health starts to improve, too. They start getting regular treatment for diabetes, infections and heart disease, for example,” Smith said. “They tend to stay in treatment longer and their outcomes tend to be much better.”

Smith, who runs a private addiction practice here, treated young middle-class kids who flocked to the Haight-Ashbury neighborhood during the “Summer of Love,” in 1967, to experiment with drugs. Many were dying of overdoses and nearly all of them were neglecting their health, he said.

“I came to a realization back then that health care was a right, not a privilege, and I’ve never changed my thinking,” Smith said. Hundreds of other doctors came to the same realization in the 1980s, when the city became ground zero in the AIDS epidemic.

Then in the 1990s, heroin returned and doctors realized that intravenous drug users were getting HIV. “People were dying all over the city,” said Dr. Judith Martin, medical director for substance abuse services at the San Francisco Department of Public Health.

Many of San Francisco’s doctors began embracing methadone, the only addiction medication back then, Martin said. Addicts who showed up at clinics to get their daily cup of methadone weren’t dying of overdoses and they weren’t contracting AIDS. As a result, Martin said, the department’s doctors are believers in addiction medicines and they’re committed to fighting the disease.

As soon as buprenorphine was approved, the department asked all of its doctors to apply for federal permission to prescribe it, and nearly all did. They were eager to help. But the prospect of fitting droves of drug-addicted new patients into their busy practices worried them.

So in 2003 the department and San Francisco General Hospital teamed up to make it easier for doctors to work with patients fighting addiction. At a cost of about $1 million per year in general tax revenue, more than 1,300 addicts have passed through the Howard Street doors and on to the care of doctors elsewhere in the city.

Once the clinic transfers patients to a primary care provider, they are removed from the rolls, allowing Howard Street’s lone doctor to keep initiating people on buprenorphine without exceeding her 100-patient limit.

San Francisco has seven methadone clinics, more than most cities its size. It also has two mobile clinics that travel to underserved neighborhoods and the jail. Three primary care sites and two pharmacies are also licensed to distribute methadone.

Getting Started

On a rainy Monday morning earlier this month, four of the eight patients in Howard Street’s Spartan waiting area sat uncomfortably on metal chairs looking like they had the flu. They were the ones scheduled to receive their first dose of buprenorphine. A handful of other patients looked much happier. They were the ones who had gotten through the rough part.

For patients who decide to quit opioids or heroin and get on buprenorphine, the first step is to stop using drugs for at least 12 hours or until they start having at least moderate withdrawal symptoms — chills, fever, body aches, watery eyes and restlessness.

That’s what they’re told when they walk in to the center on the ground floor not far from the city’s financial district, in the same building as the Department of Public Health’s mental health and residential substance abuse branch. From the Tenderloin, it’s a short walk downhill.

Patients come on their own to sign up or get referred here by a primary care doctor, a county jail or a hospital. Many want to try buprenorphine but don’t know what to expect. Some are on their second or third try at sobriety.

The first visit takes at least two hours, sometimes more, and patients are almost always filled with anxiety, said Jadine Cehand, the nurse practitioner on duty. Many are ambivalent about their decision to quit, she said. Nearly all patients are fearful of what lies ahead. “We keep telling them that they’re doing the right thing,” she said.

After the first day, patients take a dose or two of the medication home with them and come back every morning for the rest of the week to report their symptoms and get another dose. Check-ins can be less frequent the week after, depending on how they respond to the medication. “It’s amazing to see how quickly they improve,” Cehand said. “By the end of the week they come in with their hair washed and a smile on their faces.”

(Photo by a katz / Shutterstock.com)

NEXT STORY: New Software Helps Government Employees Pick Up Where Retired Staff Left Off